JANUARY 2009

Should children learn math by starting with counting?

Two roads diverged in a yellow wood, And sorry I could not travel both, And be one traveler, long I stood, And looked down one as far as I could, To where it bent in the undergrowth;

Then took the other, as just as fair, And having perhaps the better claim, Because it was grassy and wanted wear; Though as for that, the passing there, Had worn them really about the same,

And both that morning equally lay, In leaves no step had trodden black, Oh, I kept the first for another day! Yet knowing how way leads on to way, I doubted if I should ever come back.

I shall be telling this with a sigh, Somewhere ages and ages hence: two roads diverged in a wood, and I — I took the one less traveled by, And that has made all the difference.

— Robert Frost, "Road Not Taken"

I began my last month’s column with the famous quotation by the German mathematician Leopold Kronecker (1823-1891): “God made the integers; all else is the work of man.” I ended the essay with a number of questions about the way we teach beginning students mathematics, and promised to say something about an alternative approach to the one prevalent in the US.

This month’s column begins where my last left off. To avoid repeating myself, I shall assume readers have read what I wrote last month. In particular, I provided evidence in support of my thesis (advanced by others in addition to myself) that, whereas numbers and perhaps other elements of basic, K-8 mathematics are abstracted from everyday experience, more advanced parts of the subject are created and learned as rule-specified, and often initially meaningless, “symbol games.” The former can be learned by the formation of a real-world-grounded chain of cognitive metaphors that at each stage provide an understanding of the new in terms of what is already familiar. The latter must be learned in much the same way we learn to play chess: first merely following the rules, with little comprehension, then, with practice, reaching a level of play where meaning and understanding emerge.

Lakoff and Nunez describe the former process in their book Where Mathematics Comes From. Most of us can recall that the latter was the way that we learned calculus—an observation that appears to run counter to—and which I think actually does refute—Lakoff and Nunez’s claim that the metaphor-construction process they describe yields all of pure mathematics.

If indeed there are these two, essentially different kinds of mathematical thinking, that must be (or at least are best) learned in very different ways, then a natural question is where, in the traditional K-university curriculum, the one ends and the other starts. And make no mistake about it, the two forms of learning I am talking about are very different. In the first, meaning gives rise to rules; in the second, rules eventually yield meaning. Somewhere between the acquisition of the (whole) number concept and calculus, the process of learning changes from one of abstraction to linguistic creation.

Note that both can generate mathematics that has meaning in the world and may be applied in the world. The difference is that in the former, the real-world connection precedes the new mathematics, in the latter the new mathematics must be “cognitively bootstrapped” before real-world connections can be understood and applications made.

Before I go any further, I should point out that, since I am talking about human cognition here, my simplistic classification into two categories is precisely that: a simplistic classification, convenient as a basis for making the general points I wish to convey. As always when people are concerned, the world is not black-and-white, but a continuous spectrum where there are many shades of gray between the two extremes. If my monthly email inbox is anything to go by, mathematicians, as a breed, seem particularly prone to trying to view everything in binary fashion. (So was I until I found myself, first a department chair and then a dean, when I had to deal with people and university politics on a daily basis!)

In particular, it may in principle be possible for a student, with guidance, to learn all of mathematics in the iterated-metaphor fashion described by Lakoff and Nunez, where each step is one of both understanding and competence (of performance). But in practice it would take far too long to reach most of contemporary mathematics. What makes it possible to learn advanced math fairly quickly is that the human brain is capable of learning to follow a given set of rules without understanding them, and apply them in an intelligent and useful fashion. Given sufficient practice, the brain eventually discovers (or creates) meaning in what began as a meaningless game, but it is in general not necessary to reach that stage in order to apply the rules effectively. An obvious example can be seen every year, when first-year university physics and engineering students learn and apply advanced methods of differential equations, say, without understanding them—a feat that takes the mathematics majors (where the goal very definitely is understanding) four years of struggle to achieve.

Backing up from university level now, where the approach of rapidly achieving procedural competence is effective for students who need to use various mathematical techniques, what is the best way to teach beginning mathematics to students in the early grades of the schools? Given the ability of young children to learn to play games, often highly complicated fantasy games, and the high level of skill they exhibit in videogames, many of which have a complexity level that taxes most adults—and if you don’t believe me, go ahead and try one for yourself (I have and they can be very hard to master)—I guess it might be possible they could learn elementary math that way. But I’m not aware that this approach has ever been tried, and it is not clear to me it would work. In fact, I suspect it would not. One thing we want our children to learn is how to apply mathematics to the everyday world, and that may well depend upon grounding the subject in that real world. After all, a university student who learns how to use differential equations in a rule-based fashion approaches the task with a more mature mind and an awful lot of prior knowledge and experience in using mathematics. In other words, the effectiveness of the rule-based, fast-track to procedural competence for older children and adults may well depend upon an initial grounding where the beginning math student abstracts the first basic concepts of (say) number and arithmetic from his or her everyday experience.

That, after all, is—as far as we know—how our ancestors first started out on the mathematical path many thousands of years ago. I caveated that last assertion with an “as far as we know” because, of course, all we have to go on is the archeological evidence of the artifacts they left behind. We don’t know how they actually thought about their world.

How it all began

We do know our ancestors began “counting” with various kinds of artifact (notches in sticks and bones, scratches on walls of caves, presumably piles of pebbles, etc.) at least 35,000 years ago, progressing to the more sophisticated clay tokens of the Sumerians around 8,000 years ago, to the emergence of abstract numbers (and written symbols to denote them) around 6,000 or 7,000 years ago. This development, which leads first to positive whole numbers with addition and eventually to positive rationals with addition was driven, we think, by commerce—the desire/need for peoples to keep track of their possessions and to trade with one another.

It is also clear from the archeological evidence that our early mathematically-capable forebears developed systems of measurement, both of length and of area, in order to measure land, plant crops, and eventually to design and erect buildings. From a present-day perspective, this looks awfully like the beginnings of the real number system, though just when that activity became numerical to an extent we would recognize today is not clear.

Today’s US mathematics curriculum starts with the positive whole numbers and addition, and builds on to in a fairly linear fashion, through negative numbers and rationals, until it reaches the real number system as the culmination. That approach can give rise to the assumption or even the belief that the natural numbers are somehow more basic or more natural than the reals. But that is not how things unfolded historically. True, if you try to build up the real numbers, starting with the natural numbers, you are faced with a long and complicated process that took mathematicians some two thousand years of effort to figure out, completing the task as recently as the end of the nineteenth century. But that does not mean that the real numbers are a cognitively more difficult concept to acquire than the natural numbers, or that one builds cognitively on the other. Humans have not only a natural ability to abstract discrete counting numbers from our everyday experience (sizes of collections of discrete objects) but also have a natural sense of continuous quantities such as length and volume (area seems less natural), and abstraction in that domain leads to positive real numbers.

In other words, from a cognitive viewpoint (as opposed to a mathematical one), the natural numbers are neither more fundamental nor more natural than the real numbers. They both arise directly from our experiences in the everyday world. Moreover, they appear to arise in parallel, out of different cognitive processes, used for different purposes, with neither dependent on the other. In fact, what little evidence there is from present-day brain research suggests that from a neurophysiological viewpoint, the real numbers—our sense of continuous number—is more basic than the natural numbers, which appear to build upon the continuous number sense by way of our language capacity. (See the recent books and articles of researchers such as Stanislaw Dehaene or Brian Butterworth for details.)

It seems then, that when we guide our children along the first steps of the long path to mathematical thinking, assuming we want to ground those key first steps in everyday experience and build upon natural human cognitive capacities, we have two possible ways to begin: the discrete world of assessing the sizes of collections and the continuous world of assessing lengths and volumes. The first leads to the natural numbers and counting, the second to the real numbers and measurement.

Two roads diverge in an educational thicket

If we start with measurement, the counting numbers and the positive rationals arise as special points on a continuous number line. Begin with counting and the real numbers arise by way of “filling in the gaps” in the rational number line. (In both cases you have to handle negative numbers as best you can when the need arises.) Neither approach seems on the face of it to offer significant advantages over the other from a learning perspective. Take your pick and live with the curricular consequences. (True, it is mathematically much harder to construct the real numbers from the natural numbers than to recognize the natural numbers and the rationals as special points on the real line, but the issue here is not one of formal mathematical construction but human cognition, building on everyday experience.)

In the Unites States and many other countries, the choice was made—perhaps unreflectively—long ago to take our facility for counting as the starting point, and thus to start the mathematical journey with the natural numbers. But there has been at least one serious attempt to build an entire mathematical curriculum on the other approach, and that is the focus of the remainder of this essay. Not because I think one is intrinsically better than the other – though that may be the case. Rather because, whichever approach we adopt, I think it is highly likely we will do a better job, and understand better what we are doing as teachers, if we are aware of an(y) alternative approach.

Indeed, knowledge of another approach may help us guide our students through particularly tricky areas such as the multiplication concept, the topic of some of my previous columns. As Piaget observed, and others have written on extensively, helping students achieve a good understanding of multiplication in the counting-first curriculum is extremely difficult. In a measuring-first curriculum, in contrast, some of the more thorny subtleties of multiplication that plague the counting-first progression simply do not arise. Maybe the way forward to greater success in early mathematics education is to adopt a hybrid approach that builds simultaneously on both human intuitions? (Arguably this occurs anyway to some extent. US children in a counting-first curriculum use lengths, volumes, and other real-number measures in their everyday lives, and children in the real-numbers-first curriculum I am about to describe can surely count, and possibly add and subtract natural numbers, before they get to school. But I am not aware of a formal school curriculum that tries to combine both approaches.)

Whichever of the two approaches we adopt, the expressed primary goal of current K-12 mathematics education is the same the world over: to equip future citizens with an understanding of, and procedural fluency with, the real number system. In the US school system, this is done progressively, with the first stages (natural numbers, integers, rationals) taught under the name “arithmetic” and the real numbers going under the banner “algebra”. (Until relatively recently, geometry and trigonometry were part of a typical school curriculum, bringing elements of the measuring-first approach into the classroom, but that was, as we all know, abandoned, though not without a fight by its proponents.)

It is interesting to note that coverage of the real numbers as “algebra” in the US approach ensures an entirely procedural treatment, avoiding the enormous difficulties involved in constructing the concept of real numbers starting from the rationals. Eventually, even our counting-first approach has to rely on our intuitions of, and everyday experience with, continuous measurement, even if it does not start with them.

Back in the USSR

And so to the one attempt I am aware of to build an entire contemporary curriculum that starts out not with counting but with measurement. It was developed in the Soviet Union during the second half of the twentieth century, and its leading proponent was the psychologist and educator Vasily Davydov (1930-1988). Davydov based his curriculum—nowadays generally referred to by his name, though others were involved in shaping it, most notably B. Elkonin—on the cognitive theories of the great Russian developmental psychologist Lev Semenovich Vygotsky (1896-1934).

In a series of studies of the development of primates, children, and traditional peoples, Vygotsky observed that cognitive development occurs when a problem is encountered for which previous methods of solution are inadequate (Vygotsky & Luria, 1993). The Davydov mathematics curriculum is built on top of this observation, and consists of a series of carefully sequenced problems that require progressively more powerful insights and methods for their solution. This is of course quite different from the instructional approach adopted by most US teachers, which consists of an instructional lecture, with worked examples, followed by a set of exercises focused on repeated practice of the particular skill the instructor has demonstrated in class.

But that is just the first of several differences between the two approaches. Whereas the US K-12 mathematics curriculum has an understanding of and computational facility with the real numbers system as the declared end-point, the first several years are taken up with the progression through positive whole numbers, fractions, and negative integers/rationals, with the real number system covered in the later grades, primarily under the name “algebra”. In contrast, the Davydov curriculum sets its sights squarely on the real number system from the getgo. Davydov believed that starting with specific numbers (the counting numbers) leads to difficulties later on when the students work with rational and real numbers or do algebra.

I’ll come back to the focus on the real number system momentarily, but first I need to introduce another distinquishing feature of Davydov’s approach.

Davydov took account of Vygotsky’s distinction between what he called spontaneous concepts and scientific concepts. The former arise when children abstract properties from everyday experiences or from specific instances; the latter develop from formal experiences with the properties themselves.

This distinction is more or less (but not entirely) the same as the one I discussed last month between mathematics we learn by abstraction from the world and mathematics we learn in a rule-based fashion the same way we learn to play chess. For example, children who learn about the positive integers by counting collections of objects thereby acquire a spontaneous concept. Learning to play chess leads to a “scientific” understanding of the game. The point I made earlier was that in my experience, both as a learner and a teacher of advanced mathematics, the scientific approach is the most efficient, and perhaps the only way, to learn a highly abstract subject such as calculus.

In last month’s column I asked where the abstract-it-from-the-world kind of mathematics (spontaneous concepts) ends and learn-it-by-the-rules kind (scientific concepts) starts. As I have noted, that question is a naive one that obscures the fact that there is most likely a continuous spectrum of change rather than a break point. A more usefully phrased question from an educational perspective is, which parts of mathematics should we teach in a spontaneous-concepts fashion and which in a scientific-concepts way?

The accepted wisdom in the US is that the spontaneous approach is the way to go at least all the way through K-8, and maybe all the way up to grade 12. (Adopting the approach all the way to grade 12 tends to force a presentation of calculus as “a method to calculate slopes”, which I personally dislike because it reduces one of the greatest ever achievements of human intellect to a bag of procedural tricks. But that is another issue for another time.)

The Davydov curriculum adopts the scientific-concepts approach from day 1. Davydov believed that learning mathematics using a general-to-specific, “scientific” approach leads to better mathematical understanding and performance in the long run than does the spontaneous approach. His reasoning was that if very young children begin their mathematics learning with abstractions, they will be better prepared to use formal abstractions in later school years, and their thinking will develop in a way that can support the capacity to handle more complex mathematics.

He wrote (Davydov 1966), “there is nothing about the intellectual capabilities of primary schoolchildren to hinder the algebraization of elementary mathematics. In fact, such an approach helps to bring and to increase these very capabilities children have for learning mathematics.”

I should stress that Davydov’s adoption of the “scientific-concepts” approach is not at all the same as teaching mathematics in an abstract, axiomatic fashion. (This is where my analogy with learning to play chess breaks down, as do all analogies sooner or later, no matter how helpful they may be at the start; which reminds me, did I ever mention the problems that can result from introducing multiplication as repeated addition?) The Davydov approach is grounded firmly in real-world experience, and lots of it. Indeed, students spend more time at the start doing nothing but real-world activities (before doing any explicit mathematics) than is the case in the US curriculum. But when the actual mathematical concepts are introduced, it is in a scientific fashion. The students are able to link the scientific concept to their real world experience not because that concept arose spontaneously out of that experience (it did not), but because they had been guided through sufficiently rich, preparatory real-world experiences that they are able to at once see how the concept applies to the real world. (In terms of metaphors, the metaphor mapping is contructed back from the new to the old, not the other way round as in the Lakoff and Nunez framework for learning.)

How the Russian rubber hits the road

Here is how Davydov’s curriculum starts (1975a). It begins by guiding the pupils through a series of exercises to develop an increasingly sophisticated, non-numerical understanding of size (length, volume, mass). Well, that is not entirely correct. The first, “pre-mathematical” step is to prepare the pupils for those exercises.

In Grade 1, the pupils are asked to describe and define physical attributes of objects that can be compared. As I hinted a moment ago, the intention is to provide a context for the children to explore relationships, both equality and comparative. Six-year-olds typically compare physically lengths, volumes, and masses of objects, and describe their findings with statements like H < B, where H and B are unspecified quantities being compared, not objects. (At this stage the unspecified quantities are not numbers.) Notice this immediate focus on abstractions. The physical context and the act of recording mean that the elements of “abstract” algebra are introduced in a meaningful way, and are not seen by the children as abstract.

For instance, the pupils are asked how to make unequal quantities equal or how to make equal quantities unequal by adding or subtracting an amount. Starting from a volume situation recorded as H < B, the children could achieve equality by adding to volume H or subtracting from volume B. They observe that whichever action they choose, the amount added or subtracted is the same. They are told it is called the difference.

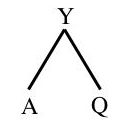

Only after they have mastered this pre-numeric understanding of size and of part-whole relationships are they presented with tasks that require quantification. For example, if they have been working with mass and have noticed that mass Y is the whole and masses A and Q are the parts that make up the whole, which they may be encouraged to express by means of a simple inverted-V diagram like this:

they can go on to write this in more formal ways:

Y = A + Q, Q + A = Y, Y – Q = A, Y – A = Q

This sets the stage for putting specific numerical values for the “variables” in order to solve equations that arise from real-world problems. (Numbers, that is, real numbers, are introduced in the second half of the first grade, as abstract measures of lengths, volumes, masses, and the like.) As a result, the pupils do not have to learn rules for solving algebraic equations; rather they become sophisticated in reasoning directly about part-whole relationships.

When the pupils get to multiplication and division, Davydov’s curriculum requires that they connect the new actions of multiplication and division with their prior knowledge of measurement and place value, as well as addition and subtraction, and to apply them to problems involving the metric system, number systems in other bases (studied in grade 1), area and perimeter, and the solution of more complex equations. In other words, the new operations come both with real world grounding and their connections to previously learned mathematics. Thee pupils have to explore the two new operations and their systemic interrelationships with previously learned concepts. They are constantly presented with problems that require them to forge connections to prior knowledge. Every new problem is different in some significant way from its predecessors and its successors. (Contrast this to the US approach where problems are presented in sets, with each set focusing on a single procedure.) As a result, the pupils must continuously think about what they are doing in order that it makes sense to them. By working through many problems designed so make them create connections between the new actions of multiplying and dividing and their previous knowledge of addition, subtraction, positional systems, and equations, they integrate their knowledge into a single conceptual system.

Thus, the Davydov curriculum is grounded in the real world, but the starting point is the continuous world of measurement rather than the discrete world of counting. I don’t know about you, but measurement and counting both seem to me to offer pretty concrete starting points for the mathematical journey. Humans are born with a capacity to make judgments and to reason about length, area, volume, etc. as well as a capacity to compare sizes of collections. Each capacity leads directly to a number concept, but to different ones: real numbers and counting numbers, respectively.

Which is better

If learning is based on the acquisition of spontaneous concepts, starting with counting, the familiar sequence from natural numbers up to the rational numbers emerges automatically. But the step to real numbers is a difficult one, both mathematically (it was not until the late nineteenth century that mathematicians really figured out that step) and cognitively (“filling in the holes in the rational line” is hard to swallow when the rational line appears not to have any holes—being what mathematicians refer to as “dense”.) With geometry (and trigonometry) no longer in vogue, the US curriculum neatly avoids the issue of what real numbers are (wisely in my view) by shifting gear at that point and sneaking in the real number system under the heading “algebra”, where the focus is on procedural matters rather than conceptual ones. (Complex numbers still remain problematical, and in fact are generally introduced, usually at college level, as a scientific concept (which is surely what it is), motivated by procedural demands.)

Clearly, the Davydov approach has no such difficulties. With the real number system as basic, integers and rational numbers are just particular points on the real number line.

Another possible advantage of the Davydov approach is that the more troublesome problems about how to successfully introduce multiplication and division that plague the start-with-counting approach to learning math—the focus of three of my columns last year—simply do not arise, since multiplication and division are natural concepts in the world of lengths, volumes, masses, etc. and part-whole relationships between them.

One feature of the Davydov approach that I personally (as a mathematician, remember, not a teacher or an expert in mathematics education, which I am not) find worrying is the absence of exercise sets focused on specific skills. Chunking and the acquisition of procedural fluency are crucial requirements for making progress in mathematics, and I don’t know of any way to achieve that than through repetitive practice. While a math curriculum that consists of little else than repetitive exercises would surely turn many more students off math than it would produce skilled numbers people, there absence seems to me just as problematic. A colleague in mathematics education tells me that Russian teachers sometimes (often?) do get their pupils to work through focused, repetitive exercise sets, and I wonder if success with a more strict Davydov curriculum might depend at least in part on parents working on repetitive exercises with their children at home.

Whether one approach is, overall, inherently better than the other, however, I simply do not know. Absent lots of evidence, no one knows. Unfortunately—and that’s a mild word to use given the high stakes of the math ed business in today’s world—there haven’t been anything like enough comparative studies to settle the matter.

One of the few US-based studies I am aware of involved an implementation of the entire three years of Davydov’s elementary mathematics curriculum in a New York school. The study was led by Jean Schmittau of the State University of New York at Binghamton. Schmittau (2004, p.20) reports that “the children in the study found the continual necessity to problem solve a considerable—even daunting—challenge, which required virtually a year to meet, as they gradually developed the ability to sustain the concentration and intense focus necessary for success. However, upon completion of the curriculum, they were able to solve problems normally given only to US high school students.”

Countering commonly made claims that in the era of cheap electronic calculators, there is no need for children to learn how to compute, and that time spent on computation actually hinders conceptual mathematical learning (for instance, you’ll find these claims made repeatedly in the 1998 NCTM Yearbook), Schmittau writes (2004, p.40), “In light of the results presented [in her paper], it is impossible to subscribe to the contention that conceptualization and the ability to solve difficult problems, are compromised by learning to compute. Not only did the children using Davydov’s curriculum attain high levels of both procedural competence and mathematical understanding, they were able to analyze and solve problems that are typically difficult for US high school students. They did not use calculators, and they resolved every computational error conceptually, without ever appealing to a “rule”. In addition, developing computational proficiency required of them both mathematical thinking and the establishing of new connections – the sine qua non of meaningful learning.”

Here again, I find myself worrying about the balance between, on the one hand, deep conceptual understanding and the ability to reason from first principles—highly important features of doing math – and, on the other hand, the need for rule-based, algorithmic methods that are practiced to the point of automatic fluency in order to progress further in the subject. The continued popularity—with parents if not their children—of commercially-offered, Saturday morning, math-skills classes suggests that I am not alone in valuing basic skills acquisition (procedural fluency), and as I mentioned once already, I often wonder if the success of some curricular experiments does not depend in part on unreported activities outside the classroom.

Another US atudy was carried out at the same time at two schools in Hawai’i by Barbara J. Dougherty and Hannah Slovin of the University of Hawai’i, and there too the researchers reported a successful outcome. They write (2004, p.301),

“Student solution methods strongly suggest that young children are capable of using algebraic symbols and generalized diagrams to solve problems. The diagrams and associated symbols can represent the structure of a mathematical situation and may be applied across a variety of settings.”

(The students used algebraic symbols coupled with diagrammatic representations like the inverted-V diagram shown above. The children in the study referred to in this quote were in the third grade.)

The secret sauce?

These two studies are encouraging. But as with all educational studies, I think we need to be cautious in interpreting them, especially if the goal is to establish educational policy and curricula. (That was not the goal of the two studies I just cited.) One issue is that studies of trial curricula—or “nonstandard” curricula that are being tested—often produce good results, for the simple reason that they are being developed and taught by enthusiastic, knowledgeable experts, with a deep understanding of the material and of educational practice. As a result, what is being measured is arguably the quality of the teaching, not the curriculum.

On the other hand, comparisons of the national performance levels achieved by nationwide curricula are also not conclusive. For instance, pupils in Singapore scored higher than the Russian students on the TIMSS, and Singapore mathematics instruction is based on counting, but not all Russian students are taught by the Davydov approach, so exactly what is being compared with what? Even if the Davydov approach is in some sense inherently superior—and when taken as a whole I think it may well be (in significant part because of the structured, integrated, exploratory way the material is introduced), the consistent high achievement of students in Singapore and Japan suggests that a counting-based approach can work just fine if taught well. (Note that the Singapore and Japanese curricula are also built on a highly structured approach that emphasizes the relationship between concepts. Both countries also place major emphasis on understanding proportionality, which is something the Davydov approach also develops, albeit in a different way.)

In fact, if we pursue that last observation a bit, we get to what I suspect is the really important factor here: teachers who have a deep understanding of basic mathematics. Hmmm, now where have I heard (and read) that before? Liping Ma, anyone?

In fact, in the context of this country, bedeviled by the incessant math wars and the intense politicization of mathematics education that drives them, my view is that debate about the curriculum and the educational theory that drives it is a distraction best avoided (at least for now). To me the real issue facing us is a starkly simple one: Teacher education. No matter what the curriculum, and regardless of the psychological and educational theory it is built upon, teaching comes down to one human being interacting with a number of (usually) younger, other human beings. If that teacher does not love what he or she is teaching, and does not understand it, deeply and profoundly, then the results are simply not going to come. The solution? Attract the best and the brightest to become mathematics teachers, teach them well, pay them at a level commensurate with their training, skills, and responsibilities, and provide them with opportunities for continuous professional development. Just what we do in (for example) the medical or engineering professions. It’s that simple.

Sources

The main source for primary materials on the Davydov curriculum is:

L. P. Steffe, (Ed.), Children’s capacity for learning mathematics. Soviet Studies in the Psychology of Learning and Teaching Mathematics, Vol. VII, Chicago: University of Chicago. Specific articles in that volume are listed below.

My brief summary of the Davydov approach is based primarily on Dougherty & Slovin 2004 and on Schmittau 2004.

The Dougherty & Slovin article describes a US-based (Hawaii) research and development project called Measure Up that uses the Davydov approach to introduce mathematics through measurement and algebra in grades 1-3.

References

Butterworth, B. (1999). What Counts: How Every Brain is Hardwired for Math, Free Press

Davydov, V.V. (1966). Logical and psychological problems of elementary mathematics as an academic subject. From D. B. Elkonin & V. V. Davydov (eds.), Learning Capacity and Age Level: Primary Grades, (pp. 54-103). Moscow: Prosveshchenie.

Davydov, V.V. (1975a). Logical and psychological problems of elementary mathematics as an academic subject. In L. P. Steffe, (Ed.), Children’s capacity for learning mathematics. Soviet Studies in the Psychology of Learning and Teaching Mathematics, Vol. VII (pp.55-107). University of Chicago.

Davydov, V.V. (1975b). The psychological characteristics of the “prenumerical” period of mathematics instruction. In L. P. Steffe, (Ed.), Children’s capacity for learning mathematics. Soviet Studies in the Psychology of Learning and Teaching Mathematics, Vol. VII (pp.109-205). University of Chicago.

Davydov, V. V., Gorbov, S., Mukulina, T., Savelyeva, M., & Tabachnikova, N. (1999). Mathematics. Moscow Press.

Dehaene, S. (1997). The Number Sense: How the Mind Creates Mathematics, Oxford University Press.

Devlin, K. (2000). The Math Gene: How Mathematical Thinking Evolved And Why Numbers Are Like Gossip, Basic Books.

Dougherty, B. & Slovin, H. Generalized diagrams as a tool for young children’s problem solving. Proceedings of the 28th Conference of the International Group for the Psychology of Mathematics Education, 2004, Vol 2 (pp.295-302). PME: Capetown, South Africa.

Ma, Liping, (1999). Knowing and Teaching Elementary Mathematics: Teachers’ Understanding of Fundamental Mathematics in China and the United States, Lawrence Erlbaum: Studies in Mathematical Thinking and Learning.

Morrow, L.J. & M.J. Kenney, M.J. (Eds,) (1998), NCTM Yearbook: The teaching and learning of algorithms in school mathematics. Reston, VA: National Council of Teachers of Mathematics.

Schmittau, J. Vygotskian theory and mathematics education: Resolving the conceptual-procedural dichotomy. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 2004, Vol.XIX, No 1(pp.19-43). Instituto Superior de Psicologia Aplicada : Lisbon, Spain.

Vygotsky, L. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard Press.

Devlin’s Angle is updated at the beginning of each month.

Mathematician Keith Devlin (email: devlin@stanford.edu) is the Executive Director of the Human-Sciences and Technologies Advanced Research Institute (H-STAR) at Stanford University and The Math Guy on NPR’s Weekend Edition. His most recent book is The Unfinished Game: Pascal, Fermat, and the Seventeenth-Century Letter that Made the World Modern, published by Basic Books.

FEBRUARY 2009

When the evidence deceives us

A few minutes calculation shows that the quadratic polynomial

generates prime numbers as values for n = 0, 1, 2, … , 39, an unbroken sequence of the first forty natural number arguments. This seems to have been noticed first by Leonard Euler in 1772. Knowing that mathematics is the science of patterns, it is tempting to conclude that the formula generates primes for all natural number arguments, but this is not the case: f(40) is composite, as are many other values.

A mathematician with some experience with prime numbers is unlikely to be “fooled” by the numerical evidence in this example, but even world-class mathematicians have on occasion been misled by far fewer cases; Pierre de Fermat among them. The nth Fermat number F(n) is obtained by raising 2 to the power n, then raising 2 to that number and adding 1 to the result, i.e.

Thus F(0) = 3, F(1) = 5, F(2) = 17, F(3) = 257, F(4) = 65,537.

These numbers are called Fermat numbers because of a claim made by Fermat in a letter written to Mersenne in 1640. Having noted that each of the numbers F(0) to F(4) is prime, Fermat wrote:

“I have found that numbers of the form F(n) are always prime numbers and have long since signified to analysts the truth of this theorem.”

For all his great abilities with numbers, however, Fermat was wrong. This was first shown conclusively by the great Swiss mathematician Leonhard Euler in 1732: F(5) = 4,294,967,297 is not prime. In fact, no prime Fermat number has been found beyond F(4).

There are many other examples where the numerical evidence can mislead us. If you have access to a computer algebra system or a multi-precision scientific calculator program (several of which you can download for free from the Web), try computing

to 30 places of accuracy. You will obtain the result 262 537 412 640 768 744 . 000 000 000 000

An integer! Amazing. Assuming you are aware of Euler’s famous identity

where exponentiation of a transcendental real number by a transcendental imaginary number yields an integer result, you might be surprised that you never came across this other one before. How come you missed it?

The answer is, the result is not an integer. Twelve decimal places all equal to zero is highly suggestive, but if you increase the precision of the calculation to 33 places, you find that

This is still an interesting answer, and you would be right to suspect that there is something special about that number 163 that makes this particular power of e so close to an integer, but I won’t go into that here. My point is simply to illustrate that computation can sometimes lead to conclusions that turn out to be incorrect. In this case the error lies in mistaking for an integer a number that is in fact transcendental.

Another coincidence, in this case most likely having no mathematical explanation, is that to ten significant figures

Here is another example where the numbers can be misleading. If you use a computer algebra system to evaluate the infinite sum

you will get the answer 1. (The half-brackets denote the “largest integer less than or equal to” function.)

But this answer is only approximate. The series actually converges to a transcendental number, which to 268 decimal places is equal to 1. In other words, you would need to calculate the numerical value to at least 269 places to determine that it is not 1, although to ensure there were no rounding errors, you would have to carry out the calculation to an even greater accuracy.

Or try this one on for size (and what a size it is in terms of accuracy). The following “equality” is correct to over half a billion digits:

But this sum, far from being an integer (conceptually far, that is!), is provably irrational, indeed transcendental. As you have probably guessed, this is a “cooked” example, related to my second example. But what an example it is!

The Mertens conjecture

A famous, and mathematically important example where the numerical evidence was misleading is the Mertens conjecture.

If you take any natural number n, then, by the fundamental theorem of arithmetic, either n is prime or else it can be expressed as a product of a unique collection of primes. For instance, for the first five non-primes,

4 = 2 x 2, 6 = 2 x 3, 8 = 2 x 2 x 2, 9 = 3 x 3, 10 = 2 x 5.

Of these, 4, 8, and 9 have prime decompositions in which at least one prime occurs more than once, while in the decompositions of 6 and 10 each prime occurs once only. Numbers divisible by the square of a prime (such as 4, 8, 9) are called square-divisible. Numbers not so divisible are called square-free. (Thus, in the prime decomposition of a square-free number, no prime will occur more than once.)

If n is a square-free natural number that is not prime, then it is a product of either an even number of primes or an odd number of primes. For example, 6 = 2 x 3 is a product of an even number of primes, while 42 = 2 x 3 x 7 is a product of an odd number of primes.

In 1832, A.F. Moebius introduced the following simple function (nowadays called the Moebius function) to indicate what type of prime factorization a number n has.

Let m(1) = 1, a special case. For all other n, m(n) is defined as follows:

If n is square-divisible, then m(n) = 0;

If n is square-free and the product of an even number of primes, then m(n) = 1;

If n is either prime, or square-free and the product of an odd number of primes, then m(n) = –1.

For example, m(4) = 0, m(5) = -1, m(6) = 1, m(42) = -1.

For any number n, let M(n) denote the result of adding together all values of m(k) for k less than or equal to n.

For example, M(1) = 1, M(2) = 0, M(3) = –1, M(4) = –1, M(5) = –2.

At tbis stage, you may like to investigate this question: What is the first value of n beyond 2 for which M(n) is zero again? Or positive again?

So far, everything looks like a nice example of elementary recreational mathematics. Matters take a decidedly more serious turn when you learn that the behavior of the function M(n) is closely related to the location of the zeros of the Riemann zeta function.

The connection was known to T.J. Stieltjes. In 1885, in a letter to his colleague C. Hermite, he claimed to have proved that no matter how large n may be, |M(n)|, the absolute value of M(n), is always less than SQRT(n).

If what Stieltjes claimed had been true, the truth of the Riemann hypothesis would have followed at once. Needless to say, then, Stieltjes was wrong in his claim, though at the time this was not at all clear. (For instance, when Hadamard wrote his now-classic and greatly acclaimed paper proving the Prime Number Theorem in 1896, he mentioned that he understood Stieltjes had already obtained the same result using his claimed inequality, and excused his own publication on the grounds that Stieltjes’ proof had not yet appeared!)

The fact that Stieltjes never did publish a proof might well suggest that he eventually found an error in his argument. At any rate, in 1897, F. Mertens produced a 50-page table of values of m(n) and M(n) for n up to 10,000, on the basis of which he was led to conclude that Stieltjes’ inequality was “very probable.” As a result Stieltjes’ inequality became known as the Mertens Conjecture. By rights, it should have been called the Stieltjes conjecture, of course, but Mertens certainly earned his association with the problem by hand-computing 10,000 values of the function.

When mathematicians brought computers into the picture, they took Mertens’ computation considerably further, eventually calculating 7.8 billion values, all of which satisfied Stieltjes’ inequality. Given such seemingly overwhelming numerical evidence, one might be forgiven for assuming the Mertens conjecture were true, but in October 1983, Hermann te Riele and Andrew Odlyzko brought eight years of collaborative work to a successful conclusion by proving otherwise.

Their result was obtained by a combination of classical mathematical techniques and high-powered computing. The computer was not used to find a number n for which |M(n)| equals or exceeds SQRT(n). Even to date, no such number has been found, and the available evidence suggests that there is no such n below 1030. Rather, they took a more circuitous route. Far too circuitous to present here, in fact. If you want to see exactly what they did, read the account in my book Mathematics: The New Golden Age, Columbia University Press 1999, pp.208-213.

Humbled but not undaunted, however, …

Examples such as the above serve as salutary reminders that when our goal is mathematical truth (certainty), numerical evidence is often at best suggestive. How much higher we set the bar in mathematics than in, say, physics, where ten decimal places of agreement between theory and experiment is generally regarded as conclusive, indeed far more than physicists usually have to settle for.

On the other hand, mathematics is for the most part far less mischievous (and hence potentially far closer to physics) than my above examples might suggest. In general, provided we exercise some reasonable caution, we can, in the words of Yogi Berra, learn a lot by just looking. Looking for, and at, computational (often numerical) evidence, that is.

In today’s era of fast, interactive computers, with computational tools such as Mathematica and Maple—not to forget search engines such as Google—we can approach some areas of mathematics in a way reminiscent of our colleagues in the natural sciences. We can make observations, collect data, and perform (computational) experiments. And we can draw conclusions based on the evidence we have obtained.

The result is a relatively new area (or form) of mathematics called Experimental Mathematics. Proof has a place in experimental mathematics, since computation can sometimes generate insights that lead to proofs. But the experimental mathematician is also willing to reach a conclusion based on the weight of evidence available. I shall say more about this new way of doing mathematics next month—when I will also note that it is actually not quite as new as might first appear.

Devlin’s Angle is updated at the beginning of each month.

Mathematician Keith Devlin (email: devlin@stanford.edu) is the Executive Director of the Human-Sciences and Technologies Advanced Research Institute (H-STAR) at Stanford University and The Math Guy on NPR’s Weekend Edition. His most recent book is The Unfinished Game: Pascal, Fermat, and the Seventeenth-Century Letter that Made the World Modern, published by Basic Books.

MARCH 2009

What is Experimental Mathematics?

In my last column, I gave some examples of mathematical hypotheses that, while supported by a mass of numerical evidence, nevertheless turn out to be false. Mathematicians know full well that numerical evidence, even billions of cases, does not amount to conclusive proof. No matter how many zeros of the Riemann Zeta function are computed and observed to have real-part equal to 1/2, the Riemann Hypothesis will not be regarded as established until an analytic proof has been produced.

But there is more to mathematics than proof. Indeed, the vast majority of people who earn their living “doing math” are not engaged in finding proofs as all; their goal is to solve problems to whatever degree of accuracy or certainty is required. While proof remains the ultimate, “gold standard” for mathematical truth, conclusions reached on the basis of assessing the available evidence have always been a valid part of the mathematical enterprise. For most of the history of the subject, there were significant limitations to the amount of evidence that could be gathered, but that changed with the advent of the computer age.

For instance, the first published calculation of zeros of the Riemann Zeta function dates back to 1903, when J.P. Gram computed the first 15 zeros (with imaginary part less than 50). Today, we know that the Riemann Hypothesis is true for the first ten trillion zeros. While these computations do not prove the hypothesis, they constitute information about it. In particular, they give us a measure of confidence in results proved under the assumption of RH.

Experimental mathematics is the name generally given to the use of a computer to run computations—sometimes no more than trial-and-error tests—to look for patterns, to identify particular numbers and sequences, to gather evidence in support of specific mathematical assertions, that may themselves arise by computational means, including search.

Had the ancient Greeks (and the other early civilizations who started the mathematics bandwagon) had access to computers, it is likely that the word “experimental” in the phrase “experimental mathematics” would be superfluous; the kinds of activities or processes that make a particular mathematical activity “experimental” would be viewed simply as mathematics. On what basis do I make this assertion? Just this: if you remove from my above description the requirement that a computer be used, what would be left accurately describes what most, if not all, professional mathematicians have always spent much of their time doing!

Many readers, who studied mathematics at high school or university but did not go on to be professional mathematicians, will find that last remark surprising. For that is not the (carefully crafted) image of mathematics they were presented with. But take a look at the private notebooks of practically any of the mathematical greats and you will find page after page of trial-and-error experimentation (symbolic or numeric), exploratory calculations, guesses formulated, hypotheses examined, etc.

The reason this view of mathematics is not common is that you have to look at the private, unpublished (during their career) work of the greats in order to find this stuff (by the bucketful). What you will discover in their published work are precise statements of true facts, established by logical proofs, based upon axioms (which may be, but more often are not, stated in the work).

Because mathematics is almost universally regarded, and commonly portrayed, as the search for pure, eternal (mathematical) truth, it is easy to understand how the published work of the greats could come to be regarded as constitutive of what mathematics actually is. But to make such an identification is to overlook that key phrase “the search for”. Mathematics is not, and never has been, merely the end product of the search; the process of discovery is, and always has been, an integral part of the subject. As the great German mathematician Carl Friedrich Gauss wrote to his colleague Janos Bolyai in 1808, “It is not knowledge, but the act of learning, not possession but the act of getting there, which grants the greatest enjoyment.”

In fact, Gauss was very clearly an “experimental mathematician” of the first order. For example, his analysis—while still a child—of the density of prime numbers, led him to formulate what is now known as the Prime Number Theorem, a result not proved conclusively until 1896, more than 100 years after the young genius made his experimental discovery.

For most of the history of mathematics, the confusion of the activity of mathematics with its final product was understandable: after all, both activities were done by the same individual, using what to an outside observer were essentially the same activities—staring at a sheet of paper, thinking hard, and scribbling on that paper. But as soon as mathematicians started using computers to carry out the exploratory work, the distinction became obvious, especially when the mathematician simply hit the ENTER key to initiate the experimental work, and then went out to eat while the computer did its thing. In some cases, the output that awaited the mathematician on his or her return was a new “result” that no one had hitherto suspected and might have no inkling how to prove.

What makes modern experimental mathematics different (as an enterprise) from the classical conception and practice of mathematics is that the experimental process is regarded not as a precursor to a proof, to be relegated to private notebooks and perhaps studied for historical purposes only after a proof has been obtained. Rather, experimentation is viewed as a significant part of mathematics in its own right, to be published, considered by others, and (of particular importance) contributing to our overall mathematical knowledge. In particular, this gives an epistemological status to assertions that, while supported by a considerable body of experimental results, have not yet been formally proved, and in some cases may never be proved. (It may also happen that an experimental process itself yields a formal proof. For example, if a computation determines that a certain parameter p, known to be an integer, lies between 2.5 and 3.784, that amounts to a rigorous proof that p = 3.)

When experimental methods (using computers) began to creep into mathematical practice in the 1970s, some mathematicians cried foul, saying that such processes should not be viewed as genuine mathematics—that the one true goal should be formal proof. Oddly enough, such a reaction would not have occurred a century or more earlier, when the likes of Fermat, Gauss, Euler, and Riemann spent many hours of their lives carrying out (mental) calculations in order to ascertain “possible truths” (many but not all of which they subsequently went on to prove). The ascendancy of the notion of proof as the sole goal of mathematics came about in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when attempts to understand the infinitesimal calculus led to a realization that the intuitive concepts of such basic concepts as function, continuity, and differentiability were highly problematic, in some cases leading to seeming contradictions. Faced with the uncomfortable reality that their intuitions could be inadequate or just plain misleading, mathematicians began to insist that value judgments were hitherto to be banished to off-duty chat in the university mathematics common room and nothing would be accepted as legitimate until it had been formally proved.

What swung the pendulum back toward (openly) including experimental methods, was in part pragmatic and part philosophical. (Note that word “including”. The inclusion of experimental processes in no way eliminates proofs.)

The pragmatic factor behind the acknowledgment of experimental techniques was the growth in the sheer power of computers, to search for patterns and to amass vast amounts of information in support of a hypothesis.

At the same time that the increasing availability of ever cheaper, faster, and more powerful computers proved irresistible for some mathematicians, there was a significant, though gradual, shift in the way mathematicians viewed their discipline. The Platonistic philosophy that abstract mathematical objects have a definite existence in some realm outside of Mankind, with the task of the mathematician being to uncover or discover eternal, immutable truths about those objects, gave way to an acceptance that the subject is the product of Mankind, the result of a particular kind of human thinking.

The shift from Platonism to viewing mathematics as just another kind of human thinking brought the discipline much closer to the natural sciences, where the object is not to establish “truth” in some absolute sense, but to analyze, to formulate hypotheses, and to obtain evidence that either supports or negates a particular hypothesis.

In fact, as the Hungarian philosopher Imre Lakatos made clear in his 1976 book Proofs and Refutations, published two years after his death, the distinction between mathematics and natural science—as practiced—was always more apparent than real, resulting from the fashion among mathematicians to suppress the exploratory work that generally precedes formal proof. By the mid 1990s, it was becoming common to “define” mathematics as a science—”the science of patterns”.

The final nail in the coffin of what we might call “hard-core Platonism” was driven in by the emergence of computer proofs, the first really major example being the 1974 proof of the famous Four Color Theorem, a statement that to this day is accepted as a theorem solely on the basis of an argument (actually, today at least two different such arguments) of which a significant portion is of necessity carried out by a computer.

The degree to which mathematics has come to resemble the natural sciences can be illustrated using the example I have already cited: the Riemann Hypothesis. As I mentioned, the hypothesis has been verified compuationally for the ten trillion zeros closest to the origin. But every mathematician will agree that this does not amount to a conclusive proof. Now suppose that, next week, a mathematician posts on the Internet a five-hundred page argument that she or he claims is a proof of the hypothesis. The argument is very dense and contains several new and very deep ideas. Several years go by, during which many mathematicians around the world pore over the proof in every detail, and although they discover (and continue to discover) errors, in each case they or someone else (including the original author) is able to find a correction. At what point does the mathematical community as a whole declare that the hypothesis has indeed been proved? And even then, which do you find more convincing, the fact that there is an argument—which you have never read, and have no intention of reading—for which none of the hundred or so errors found so far have proved to be fatal, or the fact that the hypothesis has been verified computationally (and, we shall assume, with total certainty) for 10 trillion cases? Different mathematicians will give differing answers to this question, but their responses are mere opinions.

With a substantial number of mathematicians these days accepting the use of computational and experimental methods, mathematics has indeed grown to resemble much more the natural sciences. Some would argue that it simply is a natural science. If so, it does however remain, and I believe ardently will always remain, the most secure and precise of the sciences. The physicist or the chemist must rely ultimately on observation, measurement, and experiment to determine what is to be accepted as “true,” and there is always the possibility of a more accurate (or different) observation, a more precise (or different) measurement, or a new experiment (that modifies or overturns the previously accepted “truths”). The mathematician, however, has that bedrock notion of proof as the final arbitrator. Yes, that method is not (in practice) perfect, particularly when long and complicated proofs are involved, but it provides a degree of certainty that the natural sciences rarely come close to.

So what kinds of things does an experimental mathematician do? (More precisely, what kinds of activity does a mathematician do that classify, or can be classified, as “experimental mathematics”?) Here are a few:

- Symbolic computation using a computer algebra system such as Mathematica or Maple

- Data visualization methods

- Integer-relation methods, such as the PSLQ algorithm

- High-precision integer and floating-point arithmetic

- High-precision numerical evaluation of integrals and summation of infinite series

- Iterative approximations to continuous functions

- Identification of functions based on graph characteristics.

Want to know more? As a mathematician who has not actively worked in an experimental fashion (apart from the familiar trial-and-error playing with ideas that are part and parcel of any mathematical investigation), I did, and I recently had an opportunity to learn more by collaborating with one of the leading figures in the area, the Canadian mathematician Jonathan Borwein, on an introductory-level book about the subject. The result was published recently by A.K. Peters: The Computer as Crucible: An Introduction to Experimental Mathematics. This month’s column is abridged from that book.

We both hope you enjoy it.

Devlin’s Angle is updated at the beginning of each month.

Mathematician Keith Devlin (email: devlin@stanford.edu) is the Executive Director of the Human-Sciences and Technologies Advanced Research Institute (H-STAR) at Stanford University and The Math Guy on NPR’s Weekend Edition. His most recent book for a general reader is The Unfinished Game: Pascal, Fermat, and the Seventeenth-Century Letter that Made the World Modern, published by Basic Books.

APRIL 2009

Stanislaw Ulam—a Great American

This month (April 3, to be precise) marks the 100th anniversary of the birth of one of the most remarkable and influential men of the twentieth century: Stanislaw Ulam.

Ulam was a brilliant Polish mathematician who came to this country at the start of the Second World War, became a leading figure in the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos, New Mexico, the top secret project to develop the nuclear weapon that ended that war, and, together with Edward Teller, worked out the design of the thermonuclear weapons that were at the heart of the Cold War. But inventing the H-bomb was just one of many remarkable things he did.

He was one of those amazing people who did important work in many areas of mathematics—number theory, set theory, ergodic theory, and algebraic topology.

But his real strength was in his incredible ability to see things in a novel way. For example, during the war, when he was at the University of Wisconsin, his friend John von Neumann invited him to join him on a secret project in New Mexico. But he wouldn’t say what it was. So Ulam went to the university library and checked out a book on New Mexico, and looked at the book’s check-out card. It listed the names of all the scientists who had mysteriously disappeared from the university, and by looking at what they were experts in, Ulam was able to figure out what the project was probably about. He himself then joined the Manhattan Project. That was in 1943.

At Los Alamos, Ulam showed Edward Teller’s early model of the hydrogen bomb was inadequate, and suggested a better method. He realized that you could put all the H-bomb’s components inside one casing, stick a fission bomb at one end and thermonuclear material at the other, and use mechanical shock from the fission bomb to compress and detonate the fusion fuel. With a further modification by Teller, who saw that radiation from the fission bomb would compress the thermonuclear fuel much more efficiently than mechanical shock, that became the standard way to build an H-bomb.

It’s a little known fact that Ulam and Teller applied for a patent on their design. I’m not sure if the patent was ever granted, but if it was and you want to build an H-bomb, you’d better make sure you get a license on the patent.

Another Ulam invention at Los Alamos was what we call the Monte Carlo method for solving complicated mathematical problems—originally the integrals that arise in the theory of nuclear chain reactions. The method gets its name from the fact that you use a computer to make lots of random guesses, and then use statistical techniques to deduce the correct answer from all the guesses. It’s a great idea. These days the Monte Carlo method is used all over science and engineering to solve problems that would take too long to solve by other methods.

Perhaps the most amazing of Ulam’s many suggestions was something called nuclear pulse propulsion. This is where you detonate a series of small, directional nuclear explosives against a large steel pusher plate attached to a spacecraft with shock absorbers.

Yes, you heard me right. Don’t be fooled by the fact that this is the April column. This was not only a serious proposal, but it was taken seriously by the US government, who instigated the top-secret Project Orion to build such a spacecraft in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

In theory, such a propulsion system would generate about twelve times the thrust of the Space Shuttle’s main engine. The spacecraft would be a lot bigger than the Shuttle, mind, and could carry over 200 people. It would get to Mars and back in four weeks, compared to 12 months for NASA’s current chemically-powered rocket-craft, and it could visit Saturn’s moons in a seven-month mission, something that would take about nine years using current NASA technologies.

A lot of progress was made during the course of the project, particularly on crew shielding and pusher-plate design, and the system appeared to be entirely workable when the project was shut down in 1965.

Why was it shut down? The main reason given was that the Partial Test Ban Treaty made it illegal.

Some people in the know have since suggested that President Kennedy initiated the Apollo program not only in response to the launch of Sputnik, but also to buy off the people who wanted to continue working on Orion.

Another Ulam idea that attracts a lot of interest these days is one of a number of so-called Singularity Events that have been contemplated. The one that tends to get the most press coverage these days is the supposed date when computers surpass people in intelligence, but Ulam’s singularity is different. In a conversation with von Neumann in 1958, he speculated that, because the progress of technology—and changes in the way we lives our lives—is constantly accelerating, there will come a point when we cannot keep up, and there will be what mathematicians call a singularity. But this time, it won’t be a singularity in a physical system but in human history. So human affairs, as we know them, could not continue. You and I probably won’t experience this. But our children might.

Ulam died in 1984. I never met him, but I did once occupy his office. In 1965, Ulam became a professor at the University of Colorado in Boulder, and in 1980 I spent the summer there. Ulam had remained a consultant at Los Alamos ever since the war, and used to spend part of each year there. That’s where he was when I arrived, so his office in the Math Department was available, and they gave it to me.

So what sense of the man did I get from occupying his office? None whatsoever. It was completely empty apart from a single calculus textbook that I assume he had used to teach a course. But on reflection, maybe that does say something about him. When the subject of the invention of nuclear weapons comes up, the names that get bandied about are Oppenheimer and Teller. Ulam is rarely mentioned. Yet his contribution was no less than either of the two others. He was, it seems, a man more interested in the ideas themselves than the public recognition his work could bring him. Certainly, my Boulder colleagues who did know him speak warmly of him. In an era when Britney Spears and Paris Hilton are two of the most famous Americans on the planet, I’ll vote for Stan Ulam as one of the greatest Americans of all time.

Devlin’s Angle is updated at the beginning of each month.

Mathematician Keith Devlin (email: devlin@stanford.edu) is the Executive Director of the Human-Sciences and Technologies Advanced Research Institute (H-STAR) at Stanford University and The Math Guy on NPR’s Weekend Edition. His most recent book for a general reader is The Unfinished Game: Pascal, Fermat, and the Seventeenth-Century Letter that Made the World Modern, published by Basic Books.

MAY 2009

Do you believe in fairies, unicorns, or the BMI?

Take a look at the guy in the photo. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, he is overweight. They base this classification on a number called the body mass index, or BMI. Also overweight, according to this CDC endorsed metric, are athletes and movie stars Kobe Bryant, George Clooney, Matt Damon, Johnny Depp, Brad Pitt, Will Smith, and Denzel Washington. Tom Cruise scored even worse, being classified as downright obese, as was Arnold Shwarzenegger when he was a world champion body-builder. With definitions like that, no wonder Americans think of themselves as having an overweightness epidemic. (Using the CDC’s BMI measure, 66 percent of adults in the United States are considered overweight or obese.)

Yes, it’s that time of year again, when I go for my annual physical. I know the routine. My body mass index regularly comes out at around 25.1, putting me just into the “overweight category,” and the doctor sends me a fact sheet telling me I need to lose weight, exercise more, and watch my diet. Notwithstanding that fact that the person he has just examined has a waist of 32 inches, rides a bicycle in the California mountains between 120 and 160 miles a week, competes regularly in competitive bicycle events up to 120 miles, does regular upper-body work, has a resting pulse of 59 beats per minute, blood pressure generally below 120/80, healthy cholesterol levels, and eats so much broccoli I would not be surprised to wake up one morning to find it sprouting out of my ears.

(Yes, that really is me in the—recent—photo. No, I’m not a “fitness junkie”. And I am certainly not a professional athlete. I’m just a fairly ordinary guy who was lucky to be born with good genes and who likes being outdoors on my bike when the weather is nice, and I have a competitive streak that makes me want to race every now and then. A not atypical Californian academic, in fact.)

Why do we have this annual BMI charade? Why would otherwise well-educated medical professionals ignore the evidence of their own eyes? Because the BMI is one of those all-powerful magic entities: a number. And not just any number, but one that is generated by a mathematical formula. So it has to be taken seriously, right?

Sadly, despite that fact that completion of a calculus course is a necessary prerequisite for entry into medical school, the medical profession often seems no less susceptible than the general population to a misplaced faith in anything that looks mathematical, and at times displays unbelievable naivety when it comes to numbers.

(Actually, my own physician is smarter than that. I chose him because he is every bit as compulsive an outdoorsy, activities person as I am, and he seems to know that the BMI routine we go through is meaningless, though the system apparently requires that he play along and send me the “You need to lose weight and exercise more” letter, despite our having spent a substantial part of the consultation discussing our respective outdoors activities.)

So what is the BMI? A quick web search on “BMI” or “body mass index” will return hundreds of sites, many of which offer calculators to determine your BMI. All you do is feed in your height and your weight, and out comes that magic number. Many of the sites also give you a helpful guide so you can interpret the results. For instance, the CDC website gives these ranges:

below 18.5 = Underweight

18.5 to 24.9 = Ideal

25.0 to 25.9 = Overweight

30.0 and above = Obese

(Tom Cruise, with a height of 5’7″ and weight of 201 lbs, has a body mass index of 31.5, while the younger Schwarzenegger, at just over six feet tall and about 235 pounds, had a BMI over 31. The figures I quote for athletes and movie stars are from data available on the web, and I believe they are accurate, or were when the information was entered.)

Some sites even tell you how this mystical number is calculated:

BMI = weight in pounds/(height in inches x height in inches) x 703

Hmmm. No mention of waist-size here? Or rump? That’s odd. Isn’t the amount of body fat you carry related to the size belt you need to wear or how baggy is the seat of the jeans the belt holds up?

And what about the stuff inside the body? One thing all those “overweight” and “obese” athletes and movie stars have in common is that they have very little fat and a lot of muscle, and possibly also stronger, healthier bones. Now, a quick web-search reveals that mean density figures for these three body component materials are: fat 0.9 gm/ml, muscle 1.06 gm/ml, and bone 1.85. In other words, the less fat you have, and the more your body weight is made up of muscle and bone, the greater the numerator in that formula, and the higher your BMI.

In other words, if you are a fit, healthy individual with little body fat but strong bones and lots of muscle, the CDC (and other medical authorities) will classify you as overweight. Note the absurdity of the whole approach. If I actually did take my physician’s BMI-triggered, form-letter advice and exercise more, I would put on even more muscle and lose even more of what little body fat I have, and my BMI would increase! With a medical profession like that, who needs high cholesterol as an enemy?

Admittedly, those same authorities also say that a male waistline of 40 inches and a female waistline of 35 inches are where “overweight” begins. But this of course is totally inconsistent with their claim that the BMI is a reliable indicator of excess body fat. In contrast, it is consistent with my observation that it is the density of the stuff inside the body that is key, not the body weight. If you ignore that wide variation in densities, then of course you will end up classifying people with 32 inch waists as overweight. Yet this blatant inconsistency does not seem to cause anyone to pause and ask if there is not something just a little odd going on here. Isn’t it time to inject some science into this part of medical practice?

Time to take a look at that BMI formula and ask where it came from. I’ve already noted that it ignores waistline, rump-size, and the different densities of fat, muscle, and bone. Next question: Why does it mysteriously square the height? What possible scientific reason could there be to square someone’s height for heaven’s sake? (Multiplying height by girth at least has some rationale, as it would give an indication of total body volume, but it would put girth into the denominator in the formula, which is not what you want.) But height squared? Beats me.

Then there is that mysterious number 703. Most websites simply state it as if it were some physical constant. A few make the helpful remark that it is a “conversion factor.” But I could not find a single source that explains what exactly it is converting. It did not take long to figure it out, however. The origins of the BMI, of which more later, goes back to a Belgian mathematician. The original formula would thus have been in metric units, say

BMI = weight in kilograms/(height in meters x height in meters)

To give an equivalent formula in lbs and inches, you need to solve the following equation for C

1lb/(1in x 1in) x C = 0.4536kg/(0.0254m x 0.0254m)

which gives C = 703 (to the nearest whole number).

Well that at least explains the 703. Sort of. But given that the formula is self-evidently just a kludge, why not round it to 700. Stating it as 703 gives an air of accuracy the formula cannot possibly merit, and suggests that the folks who promote this piece of numerological nonsense either have no real understanding of numbers or they want to blind us by what they think we will accept as science.

Another question: Why is the original metric formula expressed in terms of kilograms and meters? Why not grams and centimeters? Or some other units? Well, given the scientific absurdity of dividing someone’s weight by the square of their height, it really doesn’t matter what the units are. I suspect the ones chosen were so that the resulting number comes out between 1 and 100, and thus looks reassuringly like a percentage. I’m beginning to suspect my “blind-us-with-science” conspiracy theory may be right after all.

So which clown first dreamt up this formula and why? Well, it was actually no clown at all, but one of the smartest mathematicians in history: the Belgian polymath Lambert Adolphe Jacques Quetelet (1796–1874). Quetelet received a doctorate in mathematics from the University of Ghent in 1819, and went on to do world class work in mathematics, astronomy, statistics, and sociology. Indeed, he was one of the founders of both these last two disciplines, being arguably the first person to use statistical methods to draw conclusions about societies.

It is to Quetelet that we can trace back that important figure in twentieth century society, the “average man.” (You know, the one with 2.4 children.) He (Quetelet, not the average man) realized that the most efficient way to organize society, allocate resources, etc. was to count and measure the population, using statistical methods to determine the (appropriate) “averages”. He looked for mathematical formulas that would correlate, numerically, with those “average citizens.”