JANUARY 2007

DNA math and the end of innocence

In September and October last year, I devoted this column to a discussion of the reliability calculations that accompany the use of DNA profiling in criminal investigations and in court cases. My beef was not the math—which for the most part is non-debatable. (The one exception here is that there is an unresolved debate between frequentists and Bayesians as to what is the most appropriate calculation to perform when it comes to presenting DNA profile evidence in court following a Cold Hit identification of the defendant.) Rather I was concerned at the way mathematics was sometimes presented in such cases, and in what I believe is a significant likelihood that judges and jurors would misunderstand the math, perhaps even to the extent of reaching an unjust verdict. (I actually got into this whole DNA business when a lawyer asked me to help prepare a submission to help judges understand the often highly subtle issues involved.)

Some interesting correspondence ensued, ranging from those who broadly shared my concerns to others who were clearly affronted that anyone should question the current practice. But when that died down, I thought the matter was over, and apart from working from time to time on a largely descriptive paper on the subject (available in unfinished—and hence unpolished—form, doubtless with some errors, at http://www.stanford.edu/~kdevlin/papers.html ) I moved on to other things.

But it seems that I must have come too close to the mark for some people. A few days ago, a colleague pointed me to the blog of a legal consultant who had posted a lengthy commentary on my two columns.

Now, as a scientist, I am used to debate and disagreement. But usually this takes the form of one party analyzing what the other has said or written. Having clearly strayed into non-scientific territory, the game was clearly played differently. Instead of analyzing my two articles, the blogger started out by stating I had claimed something that appeared nowhere in my article, and indeed is flat counter to the much more detailed version of my columns that appears in the unfinished paper just referenced. (In brief, he took statements I had made about how laypeople often present and understand certain probabilities, and then proceeded to demonstrate that those lay beliefs were false—which indeed they are, being counter to what I had written in my more substantial account referenced above). The desired intention of such a strategy is, of course, that the average reader will then discount the entire original article. This is a familiar rhetorical device people adopt when faced with an argument that leads to a conclusion they don’t like but are unable to counter on its merits. Proponents of intelligent design do it all the time.

It would of course make this column a whole lot juicier if I were to provide a link to the blog in question, but I’m not going to provide free publicity for such gross misrepresentation. Those who choose to will clearly be able to find it, and those who want to dig deeply enough can read all the components of this episode and see for themselves exactly what is going on.

But here is where I am going with this. (Like anyone who writes a lot, particularly for diverse audiences, I’ve had my share of attacks and usually I just ignore them.) Time was when mathematicians could stay clear of the political, legal, military, and quasi-religious realms (the latter as in the ID movement). At least, most of us felt we could. But mathematics has now permeated most walks of life to an extent that we can no longer claim to be separate. Those axiom-based, pure abstractions we work with connect to the world and have real consequences in the world.

Homeland Security uses mathematics to make daily threat assessments. The military uses mathematics to plan its actions. Political parties uses mathematics to plan and run election campaigns. Marketers use mathematics to plan advertising campaigns. Global corporations use mathematics in their strategic planning. Two presidential elections ago, what a statistical analysis subsequently demonstrated beyond any doubt to be a major electoral irregularity in one Florida county, swung an election and changed the course of world history in what we now see to be major way. Doubtless there are people dead today who would have been alive had that statistical analysis been carried out sooner (and understood by those who make the decisions on such matters). (There may also have been people now alive who would have been dead had that election turned out otherwise; we can never know what that alternative world-line would have led to.) Future elections are likely to depend on the security and integrity of automatic voting systems that only mathematics can supply and verify. And, to bring my column full circle, we must now accept that we and our subject are now part of the criminal justice system.

If ever there was a time when physicists could stand aloof from the messy everyday world, that era came to an end when the first atomic bomb was detonated. It may have been an illusion that we mathematicians were able to remain “pure” for a few decades longer, but illusion or not, we can no longer maintain such an attitude.

Outside of mathematics, arguments are not conducted, and decisions are not made, on the basis of logical correctness, as is ultimately the case in our chosen world. In the world outside mathematics, rhetoric rules. It’s all about convincing others—regardless how that end is achieved. We’d better get used to it; and if we want our voice to be heard, we’d better get good at it.

Devlin’s Angle is updated at the beginning of each month.

Mathematician Keith Devlin (email: devlin@csli.stanford.edu) is the Executive Director of the Center for the Study of Language and Information at Stanford University and The Math Guy on NPR’s Weekend Edition. Devlin’s most recent book, THE MATH INSTINCT: Why You’re a Mathematical Genius (along with Lobsters, Birds, Cats, and Dogs) was published last year by Thunder’s Mouth Press.

FEBRUARY 2007

How to stabilize a wobbly table

You are in a restaurant and you find that your table wobbles. What do you do? Most people either put up with it, or they attempt to correct the problem by pushing a folded table napkin under one of the legs. But mathematicians can go one better. A couple of years ago, four mathematicians published a research paper in which they proved that if you rotate the table about its center, you will always find an orientation where the table is perfectly stable.

This problem—as a math problem—has been around since the 1960s, when a British mathematician called Roger Fenn first formulated it, presumably while in a restaurant sitting at a wobbly table.

In 1973, the famous math columnist Martin Gardner wrote about the problem in his Scientific American column, presenting a short, clever, intuitive argument to show how rotation will always stop the wobble. Here is that argument.

Two caveats. This only works for a table with equal legs, where the wobble is caused by an uneven floor. If the table has uneven legs, you probably need the folded napkin. Also, the floor can be bumpy but has to be free of steps—if the table is on a staircase, as you often find in outdoor cafes in Tuscan hill towns like San Gimignano, the math doesn’t work. But then, if you are sitting on a restaurant terrace in Tuscany, who cares?

However uneven the floor, a table will always rest on at least three legs, even if one leg is in the air. Suppose the four corners are labeled A, B, C, D going clockwise round the table, and that leg A is in the air. If the floor were made of, say, sand, and you were to push down on legs A and B, leaving C and D fixed, then you could bring A into contact with the floor, but leg B would now extend into the sand. Okay so far?

Here comes the clever part. Since all four legs are equal, instead of pushing down on one side of the table, you could rotate the table clockwise through 90 degrees, keeping legs B, C and D flat on the ground, so that it ends up in the same position as when you pushed it down, except it would now be leg A that is pushed into the sand and legs B, C, and D are all resting on the floor. Since leg A begins in the air and ends up beneath the surface, while legs B, C, and D remain flat on the floor, at some point in the rotation leg A must have first come into contact with the ground. When it does, you have eliminated the wobble.

This argument seems convincing, but making it mathematically precise turned out to be fairly hard. (Not that the problem attracted a great deal of attention—I doubt it was even considered as a possible Millennium Problem.) In fact, it took over 30 years to figure it out. The solution, presented in the 2005 paper Mathematical Table Turning Revisited, by Bill Baritompa, Rainer Loewen, Burkard Polster, and Marty Ross, is available online at

http://arxiv.org/abs/math/0511490

As most regular readers of this column will have guessed immediately, the result follows from the Intermediate Value Theorem. But getting it to work proved much harder than some other equally cute, real-world applications of the IVT, such as the fact that at any moment in time, there is always at least one location on the earth’s surface where the temperature is exactly the same as at the location diametrically opposite on the other side of the globe.

As the authors of the 2005 solution paper observe, “for arbitrary continuous ground functions, it appears just about impossible to turn [the] intuitive argument into a rigorous proof. In particular, it seems very difficult to suitably model the rotating action, so that the vertical distance of the hovering vertices depends continuously upon the rotation angle, and such that we can always be sure to finish in the end position.”

The new proof works provided the ground never tilts more than 35 degrees. (If it did, your wine glass would probably fall over and the pasta would slide off your plate, so in practice this is not much of a limitation.)

Is the theorem any use? Or is it one of those cases where the result might be unimportant but the math used to solve it has other, important applications? I have to say that, other than the importance of the IVT itself, I can’t see any application other than fixing wobbly tables. Though I guess it does demonstrate that mathematicians do know their tables.

Devlin’s Angle is updated at the beginning of each month.

Mathematician Keith Devlin (email: devlin@csli.stanford.edu) is the Executive Director of the Center for the Study of Language and Information at Stanford University and The Math Guy on NPR’s Weekend Edition. Devlin’s most recent book, THE MATH INSTINCT: Why You’re a Mathematical Genius (along with Lobsters, Birds, Cats, and Dogs) was published last year by Thunder’s Mouth Press.

MARCH 2007

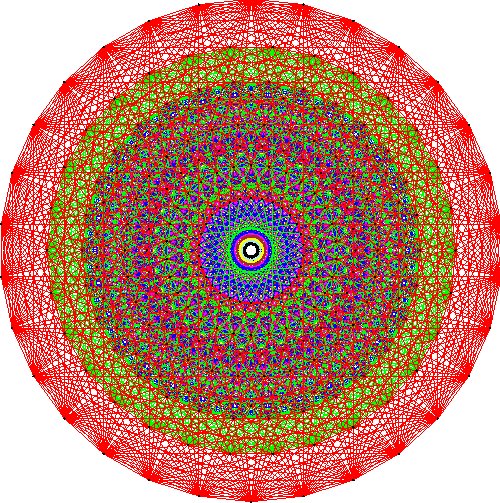

E8 Mapped

See www.aimath.org/E8/ for details.

Devlin’s Angle is updated at the beginning of each month.

Mathematician Keith Devlin (email: devlin@csli.stanford.edu) is the Executive Director of the Center for the Study of Language and Information at Stanford University and The Math Guy on NPR’s Weekend Edition. Devlin’s most recent book, THE MATH INSTINCT: Why You’re a Mathematical Genius (along with Lobsters, Birds, Cats, and Dogs) was published last year by Thunder’s Mouth Press.

APRIL 2007

Finding Musical Beauty in Euler’s Identity

This month’s column presented me with a major dilemma. Since this month marks the 300th anniversary of the birth of Leonhard Euler, how could I not write about that? Besides being the most prolific mathematician of all time in terms of written output, to my mind, and that of others, this great Swiss mathematician is one of the four greatest mathematicians of all time (the others being Archimedes, Newton, and Gauss). The trouble was, I knew that every other math writer would cover the same story!

So I hummed and ahhed, and hestitated. As a result, the middle of the month came along and still I had not written my column. But the upside of such procrastination is that eventually I noticed that no one else seemed to have written about singing Euler. That’s right, putting Euler’s mathematics to music. So, finding myself with an opening, here is my contribution to the celebration of Euler’s birth.

I have written before in this column (October, 2004) that I believe Euler’s identity

ei pi = – 1

to be the most beautiful mathematical equation of all time, the mathematical equivalent of Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa or Michaelangelo’s David. Here, shortened and paraphrased, is what I wrote then:

The number 1, that most concrete of numbers, is the beginning of counting, the basis of all commerce, engineering, science, and music. As 1 is to counting, pi is to geometry, the measure of that most perfectly symmetrical of shapes, the circle—though like an eager young debutante, pi has a habit of showing up in the most unexpected of places. As for e, to lift her veil you need to plunge into the depths of calculus—humankind’s most successful attempt to grapple with the infinite. And i, that most mysterious square root of -1, surely nothing in mathematics could seem further removed from the familiar world around us.

Four different numbers, with different origins, built on very different mental conceptions, invented to address very different issues. And yet all come together in one glorious, intricate equation, each playing with perfect pitch to blend and bind together to form a single whole that is far greater than any of the parts. A perfect mathematical composition.

The beauty I was referring to in that passage is, of course, mathematical beauty. But true beauty challenges us to find different representations, different interpretations. My comparison to music was intended as just that—a comparison. But can that be taken further? Is it possible to really capture (or at least reflect) some of the mathematical beauty of Euler’s famous identity in song? I believe the answer is yes, and that it has already been done.

Some months ago, a remarkable group of women in Santa Cruz, California, who perform together under the name of ZAMBRA, put their collective talents together to interpret Euler’s identity in song. You can hear the result for yourself at www.folkplanet.com/zambra/, where you will also hear them describe the process that led them to their interpretation.

Enjoy!

Devlin’s Angle is updated at the beginning of each month.

Mathematician Keith Devlin (email: devlin@csli.stanford.edu) is the Executive Director of the Center for the Study of Language and Information at Stanford University and The Math Guy on NPR’s Weekend Edition. Devlin’s most recent book, THE MATH INSTINCT: Why You’re a Mathematical Genius (along with Lobsters, Birds, Cats, and Dogs) was published last year by Thunder’s Mouth Press.

MAY 2007

The myth that will not go away

Part of the process of becoming a mathematics writer is, it appears, learning that you cannot refer to the golden ratio without following the first mention by a phrase that goes something like “which the ancient Greeks and others believed to have divine and mystical properties.” Almost as compulsive is the urge to add a second factoid along the lines of “Leonardo Da Vinci believed that the human form displays the golden ratio.”

There is not a shred of evidence to back up either claim, and every reason to assume they are both false. Yet both claims, along with various others in a similar vein, live on.

The latest math writer to fall victim to this peculiar compulsion is the author of an otherwise excellent article in Science News, Vol 171, No.18 (week of May 5, 2007). The main focus of that article is the appearance of the golden ratio in nature, which is real, substantiated, and of considerable scientific interest. So much so, in fact, that one wonders why the writer felt the need to spice up her story with falsehoods in her third sentence—for the two golden ratio claims I gave above are direct quotes from her lead.

Before I go any further I should say that my purpose is not to attack a fellow math writer. Indeed, let me confess that for many years I too fell victim to the very same compulsion, as a fairly quick search through some of my earlier writings will testify.

My first suspicions that all was not right with some of the claims made about the aesthetic appeal of the golden ratio were aroused when I admitted to myself that I personally did not find the golden rectangle the most pleasing among all rectangles. My doubts grew when tests I performed on several classes of students revealed that few people, when presented with a page of rectangles of various aspect ratios, picked out as the one they found most pleasing the golden rectangle. (Actually, given that the aspect ratio of any actual rectangle you draw can be only an approximation to a theoretical ideal, a more accurate description of my experiment would be that few people picked the rectangle that most closely approximated the theoretical ideal of a golden rectangle.)

Then I read an excellent article by the University of Maine mathematician George Markowsky, titled “Misconceptions about the golden ratio”, published in the College Mathematics Journal in January 1992. In his article, Markowsky subjected many of the common claims about the golden ratio to a fairly rigorous review, and found that quite a few of them come up decidedly short. Further evidence against many of the common claims you see made about the golden ratio were provided by writer Mario Livio in his 2002 book The Golden Ratio: The Story of PHI, the World’s Most Astonishing Number.

In my June 2004 “Devlin’s Angle” and in an article I wrote for the June 2004 issue of Discover magazine, I added my own contribution to Markowsky and Livio’s valiant attempts to inject some journalistic ethics into the scene (to wit, checking facts before going into print), but by all appearances the three of us have had little success. Particularly when novelist Dan Brown repeated many of the most ridiculous golden ratio chestnuts in his huge bestseller The Da Vinci Code. (No, I’m not giving a live link to that!)

With so many wonderful things to say about the golden ratio that are true and may be substantiated, why oh why do those myths keep going the rounds? Why do we so want to believe that, say, the ancient Greeks designed the Parthenon based on the golden ratio? (For the record, they did not; which is to say, there is not a shred of evidence that they did any such thing, and good reason to believe they did not.)

Yet the myth has undeniable appeal, even to individuals who claim to be innumerate. Radio producers, for instance. I gave a “debunking the golden ratio myths” talk at a science cafe event in San Francisco recently (Ask a Scientist), and by chance the local NPR radio station KQED sent a team to record the event for their science series Quest. The format for my talk was that I first repeated – as earnestly and breathlessly as I could – the various claims you see made about the golden ratio, followed by a fact-based dissection of each claim. I should have guessed that the clip the radio folk would choose to include in their broadcast was where I repeated the “the ancient Greeks believed . . .” story, but left out my subsequent denouncement thereof. Sigh. In the process of my trying to inject some facts into the picture, while the 120 or so people in my audience got the real story, tens of thousands of radio listeners heard me saying . . . Well, you get the picture. I dare not repeat it yet again!

Undaunted, let me sally forth once again into this mire of misinformation and try to set the record straight.

Here we go again

In the unlikely event that someone reading this article does not know what the golden ratio is, let me give the standard mathematical definition.

If you try to determine how to divide a line segment into two pieces such that the ratio of the whole line to the longer part is equal to the ratio of the longer part to the shorter, you will rapidly find yourself faced with solving the quadratic equation

x2 – x – 1 = 0

The positive root is an irrational number whose decimal expansion begins 1.618. This is the number now called the golden ratio, sometimes denoted by the Greek letter PHI, which I will refer to using the HTML-friendly notation GR

Euclid, in his book Elements, described the above construction and showed how to calculate the ratio. But he made absolutely no claims about visual aesthetics, and in fact gave the answer the decidedly unromantic name “extreme and mean ratio”. The term “Divine Proportion,” which is often used to refer to GR, first appeared with the publication of the three volume work by that name by the 15th century mathematician Luca Pacioli. (He has a lot to answer for!) Calling GR “golden” is even more recent: 1835, in fact, in a book written by the mathematician Martin Ohm (whose physicist brother discovered Ohm’s law).

There is no doubt that the GR has some interesting mathematical properties. It crops up in measurements of the pentagram (five-pointed star), the five Platonic solids, fractal geometry, certain crystal structures, and Penrose tilings.

The oft repeated claim (actually, all claims about GR are oft repeated) that the ratios of successive terms of the Fibonacci sequence tend to GR is also correct.

The GR also has a particularly elegant expansion as a repeated fraction. (This is almost explicit when you rearrange the quadratic equation that defines it.)

Turning from mathematics to the natural world, once you discount the initial throwaway lines about Leonardo Da Vinci and the ancient Greeks that the writer of the Science Newsarticle lets slip in, everything she says there about the role played by the golden ratio in plant growth is, to the best of my knowledge, correct—and it’s fascinating.

Nature does, it seem, favor the golden ratio. But not exclusively so. In my 2004 debunking article in “Devlin’s Angle” I inadvertently let yet another falsehood slip in. I claimed there that you can find the golden ratio in the growth of the Nautilus shell. Not so. The Nautilus does grow its shell in a fashion that follows a logarithmic spiral, i.e., spiral that turns by a constant angle along its entire length, making it everywhere self-similar. But that constant angle is not the golden ratio. Pity, I know, but there it is.

It’s when you leave the mathematical world and the natural world, however, that the falsehoods start to come thick and fast.

Numerous tests have failed to show up any one rectangle that most observers prefer, and preferences are easily influenced by other factors. As to the Parthenon, all it takes is more than a cursory glance at all the photos on the Web that purport to show the golden ratio in the structure, to see that they do nothing of the kind. (Look carefully at where and how the superimposed rectangle—usually red or yellow—is drawn and ask yourself: why put it exactly there and why make the lines so thick?)

Another spurious claim is that if you measure the distance from the tip of your head to the floor and divide that by the distance from your belly button to the floor, you get GR. But this nonsense. When you measure the human body, there is a lot of variation. True, the answers are always fairly close to 1.6. But there’s nothing special about 1.6. Why not say the answer is 1.603? Besides, there’s no reason to divide the human body by the navel. If you spend a half an hour or so taking measurements of various parts of the body and tabulating the results, you will find any number of pairs of figures whose ratio is close to 1.6, or 1.5, or whatever you want.

Then there is the claim that Leonardo Da Vinci believed the golden ratio is the ratio of the height to the width of a “perfect” human face and that he used GR in his Vitruvian Manpainting. While there is no concrete evidence against this belief, there is no evidence for it either, so once again the only reason to believe it is that you want to. The same is also true for the common claims that Boticelli used GR to proportion Venus in his famous painting The Birth of Venus and that Georges Seurat based his painting The Parade of a Circus on GR.

Painters who definitely did make use of GR include Paul Serusier, Juan Gris, and Giro Severini, all in the early 19th century, and Salvador Dali in the 20th, but all four seem to have been experimenting with GR for its own sake rather than for some intrinsic aesthetic reason. Also, the Cubists did organize an exhibition called “Section d’Or” in Paris in 1912, but the name was just that; none of the art shown involved the golden ratio.

Then there are the claims that the Egyptian Pyramids and some Egyptian tombs were constructed using the golden ratio. There is no evidence to support these claims. Likewise there is no evidence to support the claim that some stone tablets show the Babylonians knew about the golden ratio, and in fact there is good reason to conclude that it’s false.

Turning to more modern architecture, while it is true that the famous French architect Corbusier advocated and used the golden ratio in architecture, the claim that many modern buildings are based on the golden ratio, among them the General Secretariat building at the United Nations headquarters in New York, seems to have no foundation. By way of an aside, a small (and not at all scientific) survey I once carried out myself revealed that all architects I asked knew about the GR, and all believed that other architects used the GR in their work, but none of them had ever used it themselves. Make whatever inference you wish.

Music too is not without its GR fans. Among the many claims are: that some Gregorian chants are based on the golden ratio, that Mozart used the golden ratio in some of his music, and that Bartok used GR in some of his music. All those claims are without any concrete support. Less clear cut is whether Debussy used the Golden Ratio in some of his music. Here the experts don’t agree on whether some GR suggestive patterns that can be discerned are intended or spurious.

I could go on, but you get the picture, I hope. I’ve done my bit once again, and attempted once more to right my own previous wrongs in inadvertently adding fuel to this curious forest-fire of myths.

Just as happened last time, I anticipate receiving some truly ANGRY emails from readers incensed that I should dare question their long cherished beliefs about this particular number. (Maybe that’s why we say it is irrational?) And there we scratch the surface of what I think is a fascinating aspect of human nature. People, at least many people, seem to really WANT there to be numbers with mystical properties. So much so that they are prepared to put aside their otherwise wise insistence on evidence or proof. (Many of the emails I got last time demanded that I give proof that the golden ratio is not in the design of the Parthenon, for instance. Which is of course to get the scientific method completely backwards. The hypothesis in that case is that the GR did figure in the Greeks’ design, and that is what needs justification – and does not get. Ditto all the other spurious GR claims.) This almost religious attachment to a number, or to numbers in general, has a long history, going back at least as far as the Pythagoreans. I have a theory as to why people have this deep attachment to numbers. But I dare not put it in print for fear that it will assume a life of its own, and once out of the bottle, no one will be able to contain it.

Devlin’s Angle is updated at the beginning of each month.

Mathematician Keith Devlin (email: devlin@csli.stanford.edu) is the Executive Director of the Center for the Study of Language and Information at Stanford University and The Math Guy on NPR’s Weekend Edition. Devlin’s most recent book, THE MATH INSTINCT: Why You’re a Mathematical Genius (along with Lobsters, Birds, Cats, and Dogs) was published in 2005 by Thunder’s Mouth Press.

JUNE 2007

The trouble with math

One problem with teaching mathematics in the K-12 system—and I see it as a major difficulty—is that there is virtually nothing the pupils learn that has a non-trivial application in today’s world. The most a teacher can tell a student who enquires, entirely reasonably, “How is this useful?” is that almost all mathematics finds uses, in many cases important ones, and that what they learn in school leads on to mathematics that definitely is used.

Things change dramatically around the sophomore university level, when almost everything a student learns has significant applications.

I am not arguing that utility is the only or even the primary reason for teaching math. But the question of utility is a valid one that deserves an answer, and there really isn’t a good one. For many school pupils, and often their parents, the lack of a good answer is enough to persuade them to give up on math and focus their efforts elsewhere.

Just over a decade ago, I worked with PBS on a major six-part television series Life by the Numbers that set out to provide classroom teachers with materials to show their students the major role mathematics plays in today’s world. [The series is still available on DVD at http://www.montereymedia.com, though many of the examples are now looking decidedly dated.] But most of the mathematics referred to in the series is post K-12 level, so at best the series simply added some valuable flesh to the “The math you learn now leads on to stuff that is important” argument.

Another possibility to try to motivate K-12 students (actually, in my experience from visiting schools and talking with their teachers, it is the older pupils who are the ones more likely to require motivation, say grades 8 or 9 upward) is for professional mathematicians to visit schools. I know I am not the only mathematician who does this. There is nothing like presenting pupils with a living, breathing, professional mathematician who can provide a first-hand example of what mathematicians do in and for society.

I recently spent two weeks in Australia, as the Mathematician in Residence at St. Peters College in Adelaide. This was only the second time in my life that a high school had invited me to spend some time as a visitor, and the first time overseas—over a very large sea in fact! In both cases, the high school in question was private, and had secured private endowment funding to support such an activity. For two weeks, I spent each day in the school, giving classes. Many classes were one-offs, and I spent the time answering that “What do mathematicians do?” question. For some 11 and 12 grade classes, we met several times and I gave presentations and mini-lessons, answered questions, engaged in problem sessions, and generally got to know the students, and they me. You would have to ask the students what they got from my visit, but from my perspective (and that of the former head of mathematics at the school, David Martin, who organized my visit), they gained a lot. To appreciate a human activity such as mathematics, there is, after all, nothing that can match having a real-life practitioner on call for a couple of weeks.

Thought of on its own, such a program seems expensive. But viewed as a component of the entire mathematics education program at a school, the incremental cost of a “mathematician in residence” is small, though in the anti-educational and anti-science wasteland that is George Bush’s America it may be a hard sell in the U.S. just now. But definitely worth a try when the educational climate improves, I think. If it fails, the funds can always be diverted elsewhere.

Why do we teach math?

By chance, just before I arrived in Australia, on May 14, the national newspaper The Age published a full-page opinion piece by Marty Ross of the University of Melbourne, addressing the question, why do we teach mathematics to all students? Ross’s answer is that the primary purpose for teaching math is that it develops logical thinking. The follow-up letters published a week later rightly (in my opinion) critiqued this reason, pointing out that many subjects are just as good as mathematics for teaching logical thinking (and maybe better). History, physics, social studies come to mind immediately. Moreover, those subjects—if taught well—teach logical thinking in domains that the students perceive as far more relevant to their lives.

Sadly, none of the letters published stated what I think is the main reason why we teach mathematics: to develop mathematical thinking. Since our ancestors invented numbers about 10,000 years ago, we humans have developed a way of thinking about the world we live in (and more recently the worlds we create) using a mode of thought we call “mathematics”. It is a curious—and not well understood—blend of discrete and continuous quantitive measurement, abstract objects, abstract relations, abstract structures, rule-governed reasoning, and various other stuff. (I tried to flesh out the components in my 2000 book The Math Gene.)

I used to tell students that mathematical thinking is just “formalized common sense,” but then I realized this is not true. Sure, it seems an apt description for some of the more basic parts of mathematics, taught in the lower school grades. But it is way off target when it comes to much advanced mathematics, which is a highly specialized form of thinking—a “language game” in the sense of Wittgenstein, some would say—that in many cases is actually counter to “common sense reasoning.”

The amazing thing is that this strange way of thinking has proved to be extremely useful, in highly practical ways! Without mathematical thinking, we would still be living in caves or mud huts, breathing in the smoke from our fires. You need mathematical thinking to design and construct buildings, do science, develop technologies, and do all the other things Homo sapiens modernus takes for granted.

In fact, so important is this way of thinking to our lives, so powerful is it, and so strange—just think about it for a moment, it really is a most “unworldly” and unnatural, somewhat stilted way of thinking—that it surely must be taught to every living person. (Not to mastery; for most people, general awareness and a general competency is surely enough. There is no shortage of the dedicated experts, indeed the world has an oversupply.)

At least, that’s the way I see it.

Devlin’s Angle is updated at the beginning of each month.

Mathematician Keith Devlin (email: devlin@csli.stanford.edu) is the Executive Director of the Center for the Study of Language and Information at Stanford University and The Math Guy on NPR’s Weekend Edition. Devlin’s most recent book, THE MATH INSTINCT: Why You’re a Mathematical Genius (along with Lobsters, Birds, Cats, and Dogs) was published in 2005 by Thunder’s Mouth Press.

JULY-AUGUST 2007

The professor, the prosecutor, and the blonde with the ponytail

Just before noon on the 18th of June, 1964, in Los Angeles, an elderly lady by the name of Juanita Brooks was walking home from grocery shopping. As she made her way down an alley, she stooped to pick up an empty carton, at which point she suddenly felt herself being pushed to the ground. When she looked up, she saw a young woman with a blond ponytail running away down the alley with her purse.

Near the end of the alley, a man named John Bass saw a woman run out of the alley and jump into a yellow car. The car took off and passed close by him. Bass subsequently described the driver as black, with a beard and a mustache. He described the young woman as Caucasian, slightly over five feet tall, with dark blond hair in a ponytail.

Several days later, the LA Police arrested Janet Louise Collins and her husband Malcolm Ricardo Collins and charged them with the crime. Unfortunately for the prosecutor, neither Mrs. Brooks nor Mr. Bass could make a positive identification of either of the defendants. Instead, the prosecutor called as an expert witness a mathematics instructor at a nearby state college to testify on the probabilities that, he claimed, were relevant to the case.

The prosecutor asked the mathematician to consider 6 features pertaining to the two perpetrators of the robbery:

Black man with a beard

Man with a mustache

White woman with blonde hair

Woman with a ponytail

Interracial couple in a car

Yellow car

Next the prosecutor gave the mathematician some numbers to assume as the probabilities that a randomly selected (innocent) couple would satisfy each of those descriptive elements. For example, he instructed the mathematician to assume that the male partner in a couple is a “black man with a beard” in 1 out of 10 cases, and that the probability of a man having a mustache (in 1964) is 1 out of 4. He then asked the expert to explain how to calculate the probability that the male partner in a couple meets both requirements, “black man with a beard” and “man with a mustache”. The mathematician described the product rule for independent events, which says that, if two events are independent, then the probability that both events occur together is obtained by multiplying their individual probabilities.

According to this rule, the witness testified,

P(black man with a beard AND has a mustache) = P(black man with a beard) x P(has a mustache) = 1/10 x 1/4 = 1/(10 x 4) = 1/40

The complete list of probabilities the prosecutor asked the mathematician to assume was:

Black man with a beard: 1 out of 10

Man with mustache: 1 out of 4

White woman with blonde hair: 1 out of 3

Woman with a ponytail: 1 out of 10

Interracial couple in car: 1 out of 1000

Yellow car : 1 out of 10

Based on these figures, the mathematician then used the product rule to calculate the overall probability that a random couple would satisfy all of the above criteria, which he worked out to be 1 in 12 million.

Impressed by those long odds, the jury found Mr. and Mrs. Collins guilty as charged. But did they make the right decision? Was the mathematician’s calculation correct? Malcolm Collins said it was not, and appealed his conviction.

In 1968, the Supreme Court of the State of California handed down a 6-to-1 decision, and their written opinion has become a classic in the study of legal evidence. Generations of law students have studied the case as an example of the use (and misuse) of mathematics in the courtroom. (As you will see, it’s worrying that one supreme court justice reached a different conclusion, but at least the system worked.)

The justices said, among other things:

“We deal here with the novel question whether evidence of mathematical probability has been properly introduced and used by the prosecution in a criminal case. … Mathematics, a veritable sorcerer in our computerized society, while assisting the trier of fact in the search for truth, must not cast a spell over him. We conclude that on the record before us defendant should not have had his guilt determined by the odds and that he is entitled to a new trial. We reverse the judgment. …”

The Supreme Court’s devastating deconstruction of the prosecution’s “trial by mathematics” had three major elements:

Proper use of “math as evidence” versus improper use (“math as sorcery”). Failure to prove that the mathematical argument used actually applies to the case at hand. A major logical fallacy in the prosecutor’s claim about the extremely low chance of the defendants being innocent.

Math as evidence

The law recognizes two principal ways in which an expert’s testimony can provide admissible evidence. The expert can testify as to his or her own knowledge of relevant facts, or he or she can respond to hypothetical questions based on valid data that has already been presented in evidence. What is not allowed is for the expert to testify how to calculate an aggregate probability based on initial estimates that are not supported by statistical evidence, which is what happened in the Collins case.

The Supreme Court believed that the appeal of the “mathematical conclusion” of odds of 1 in 12 million was likely to be too dazzling in its apparent “scientific accuracy” to be discounted appropriately in the usual weighing of the reliability of the evidence. This, they opined, was mathematics as sorcery.

Was the trial court’s math correct?

A second issue was whether the math itself was correct. Even if the prosecution’s choice of numbers for the probabilities of individual features—black man with a beard, and so on —were supported by actual evidence and were 100% accurate, the calculation that the prosecutor asked the mathematician to do depends on a crucial assumption: that in the general population these features occur independently. If this assumption is true, then it is mathematically valid to use the product rule to calculate the probability that the couple who committed the crime, if they were not Mr. and Mrs. Collins, would by sheer chance happen to match the Collins couple in all of these factors.

But I doubt that any regular reader of this column would be so foolish as to assume that the six features the prosecutor gave the expert witness came even close to being independent.

Was the prosecutor’s claim valid?

The most devastating blow that the Supreme Court struck in its reversal of Mr. Collins’ conviction, however, concerned a mistake that (like the unjustified assumption of independence) occurs frequently in the application of probability and statistics to criminal trials. That mistake is usually called “the prosecutor’s fallacy,” and is a a sort of bait and switch by the prosecution, sometimes unintentional.

On the one hand, there is the prosecution’s calculation, which in spite of its lack of justification, attempts to determine

P(match) = the probability that a random couple would possess the distinctive features in question (bearded black man, with a mustache, etc.)

Ignoring the defects of the calculation, and assuming for the same of argument that P(match) truly is equal to 1 in 12 million, there is nevertheless a profound difference between P(match) and a second figure, namely

P(innocence) = the probability that Mr. and Mrs. Collins are innocent.

As the Supreme Court noted, the prosecutor in the Collins case argued to the jury that the 1 in 12 million calculation applied to P(innocence). He suggested that “there could be but one chance in 12 million that the defendants were innocent and that another equally distinctive couple actually committed the robbery.”

As the justices explained in their opinion, a “probability of innocence” calculation (even if one could presume to actually calculate such a thing) has to take into account how many other couples in the Los Angeles area also have those six characteristics. The court said, “Of the admittedly few such couples, which one, if any, was guilty of committing the robbery?”

The court went on to perform another calculation: Assuming the prosecution’s 1 in 12 million result, what is the probability that somewhere in the Los Angeles area there are at least two couples that have the six characteristics as the witnesses described for the robbers? The justices calculated that probability to be over 40 percent. Hence, it was not at all reasonable, they opined, to conclude that the defendants must be guilty simply because they have the six characteristics in the witnesses’ descriptions.

More like this – and other juicy stuff

NOTE: The above account is abridged (heavily) from the forthcoming book THE NUMBERS BEHIND NUMB3RS: Solving Crimes with Mathematics, that I have just co-written with Gary Lorden, the professor of mathematics at Caltech who is the principal mathematics advisor to the hit CBS television crime series NUMB3RS. Scheduled for publication on September 1, the book looks at some of the real-life applications of mathematics in solving and prosecuting crimes that inspired the creation of the television series. As this particular example shows, in writing the book we did not restrict ourselves to the successful applications of math in fighting crime (which is what the TV series does), though many of the examples we present are of that nature. Rather, we look at the whole range of circumstances where law enforcement agents of various kinds make use of mathematics. Some chapters focus on cases depicted in episodes of NUMB3RS, others (like the Collins case just described) look at other examples of the use of math in law enforcement.

We hope you enjoy the book.

Devlin’s Angle is updated at the beginning of each month.

Mathematician Keith Devlin (email: devlin@csli.stanford.edu) is the Executive Director of the Center for the Study of Language and Information at Stanford University and The Math Guy on NPR’s Weekend Edition. Devlin’s most recent book, THE MATH INSTINCT: Why You’re a Mathematical Genius (along with Lobsters, Birds, Cats, and Dogs) was published in 2005 by Thunder’s Mouth Press.

SEPTEMBER 2007

What is conceptual understanding?

Mathematics educators talk endlessly about conceptual understanding, how important it is (or isn’t) for effective math learning (depends what you classify as effective), and how best to achieve it in learners (if you want them to have it).

Conceptual understanding is one of the five strands of mathematical proficiency, the overall goal of K-12 mathematics education as set out by the National Research Council’s 1999-2000 Mathematics Learning Study Committee in their report titled Adding It Up: Helping Children Learn Mathematics, published by the National Academy Press in 2001.

I’m a great fan of that book, so let me say up front that I think achieving conceptual understanding is an important component of mathematics education. That appears to pit me against one of the two opposing camps in the math wars—the skills brigade—so let me even things up a bit by adding that I think many mathematical concepts can be understood only after the learner has acquired procedural skill in using the concept. In such cases, learning can take place only by first learning to follow symbolic rules, with understanding emerging later, sometimes considerably later. That probably makes me an enemy of the other camp, the conceptual-understanding-first proponents.

I do agree with practically everyone that procedural skills that are not eventually accompanied by some form of understanding are brittle and easily lost. I believe that the need for rule-based skill acquisition before conceptual understanding can develop is in fact the norm for more advanced parts of mathematics (calculus and beyond), and I’m not convinced that it is possible to proceed otherwise in all of the more elementary parts of the subject.

[LONG ASIDE: Theoretically, I think it probably is possible to achieve understanding along with skill mastery for any mathematical topic, but it would take far too long, with a likely result that the student would simply lose heart and give up long before achieving sufficient understanding. But as language creatures—the “symbolic species” to use Terrence Deacon’s term [Terrence Deacon, The Symbolic Species: The Co-Evolution of Language and the Brain, W.W. Norton, 1997]—we have a powerful ability to learn to follow symbolic rules without understanding what they mean; and as pattern recognizers with an instinct to perceive meaning in the world, once we have learned to play such a “symbol game” it generally does not take us long to figure out what it means. Chess playing is an excellent example of how learning to play by simply following the rules eventually leads to an understanding of the game. Thus, while the idea that students should “understand before they do” has a lot of appeal, it ignores that fact that nature has equipped us with a far more efficient method of learning.]

But that is not my focus here. Rather the question I am asking is, what exactly is conceptual understanding?

My problems are, I don’t really know what others mean by the term; I suspect that they often mean something different from me (though I believe that what I mean by it is the same as other professional mathematicians); and I do not know how to tell if a student really has what I mean by it.

Adding It Up defines conceptual understanding as “the comprehension of mathematical concepts, operations, and relations,” which elaborates the question but does not really answer it.

Whatever it is, how do we teach it?

The accepted wisdom for introducing a new concept in a fashion that facilitates understanding is to begin with several examples. For instance, the celebrated American mathematician R. P. Boas had the following to say on the issue, in a article titled “Can we make mathematics intelligible?”, published in the American Mathematical Monthly, Volume 88 (1981), pp.727-731:

“Suppose that you want to teach the ‘cat’ concept to a very young child. Do you explain that a cat is a relatively small, primarily carnivorous mammal with retractable claws, a distinctive sonic output, etc.? I’ll bet not. You probably show the kid a lot of different cats, saying ‘kitty’ each time, until it gets the idea. To put it more generally, generalizations are best made by abstraction from experience.”

This idea is appealing, but not without its difficulties, the primary one being that the learner may end up with a concept different from the one the instructor intended! The difficulty arises because an abstract mathematical concept generally has fundamental features different from some or even all of the examples the learner meets. (That, after all, is one of the goals of abstraction!)

An important illustration of this that has been much studied is the modern mathematical concept of a function. For instance, the Israeli mathematician and mathematics educationalist Uri Leron, in his article “Mathematical Thinking and Human Nature: Consonance and Conflict” [Proceedings of the 28th Conference of the International Group for the Psychology of Mathematics Education, 2004. (3) 217-224] wrote:

“According to the algebraic image of functions, an operation is acting on an object. The agent performing the operation takes an object and does something to it. For example, a child playing with a toy may move it, squeeze it, or color it. The object before the action is the input and the object after the action is the output. The operation is thus transforming the input into the output. The proposed origin of the algebraic image of functions is the child’s experience of acting on objects in the physical world. . . . Inherent to this image is the experience that an operation changes its input—after all, that’s why we engage it in the first place: you move something to change its place, squeeze it to change its shape, color it to change its look.

But this is not what happens in modern mathematics or in functional programming. In the modern formalism of functions, nothing really changes! The function is a “mapping between two fixed sets” or even, in its most extreme form, a set of ordered pairs. As is the universal trend in modern mathematics, an algebraic formalism has been adopted that completely suppresses the images of process, time, and change.“

Leron and others have carried out several studies demonstrating that many mathematics and computer science students at universities have formed erroneous concepts of functions; assuming in particular that applying a function to an argument changes the argument. Such is the power of the original examples, that even when presented with the correct formal definition of the general, abstract concept, the learners assume features suggested by the examples that are not part of the abstract concept. It can take an experienced instructor some time to uncover such a misconception, let alone correct it.

Thus, whereas conceptual understanding is a goal that educators should definitely strive for, we need to accept that it cannot be guaranteed, and accordingly we should allow for the learner to make progress without fully understand the concepts.

The authors of Adding It Up seem to accept this problem. Rather than insist on full understanding of the concepts, the committee explained further what they meant by “conceptual understanding” this way (p.141), “… conceptual understanding refers to an integrated and functional grasp of the mathematical ideas.”

The key term here, as I see it, is “integrated and functional grasp.” This suggests an acceptance that a realistic goal is that the learner has sufficient understanding to work intelligently and productively with the concept and to continue to make progress, while allowing for future refinement or even correction of the learner’s concept-as-understood, in the light of further experience. (It is possible I am reading something into the NRC Committee’s words that the committee did not intend. In which case I suggest that in the light of further considerations I am refining the NRC Committee’s concept of conceptual understanding!)

Enter “functional understanding”

I propose we call this relaxed notion of conceptual understanding functional understanding. It means, roughly speaking, understanding a concept sufficiently well to get by for the present. Because functional understanding is defined it terms of what the learner can do with it, it is possible to test if the learner has achieved it or not, which avoides my uncertainty about full conceptual understanding.

Since the distinction I am making is somewhat subtle, let me provide a dramatic example. As the person who invented calculus, it would clearly be absurd to say that Newton did not understand what he was doing. Nevertheless, he did not have (conceptual) understanding of the concepts that underlay calculus as we do today—for the simple reason that those concepts were not fully worked out until late in the nineteenth century, two-hundred-and-fifty years later. Newton’s understanding, which was surely profound, would be one of functional understanding. Euler demonstrated similar functional understanding of infinite sums, though the concepts that underpin his work were also not developed until later.

One of the principal reason why mathematics majors students progress far, far more slowly in learning new mathematical techniques at university than do their colleagues in physics and engineering, is that the mathematics faculty seek to achieve full conceptual understanding in mathematics majors, whereas what future physicists and engineers need is (at most) functional understanding. (Arguably most of them don’t really need that either; rather what they require is another of the five strands of mathematical proficiency, procedural fluency.) I have taught at universities where the engineering faculty insisted on teaching their own mathematics, precisely because they wanted their students to progress much faster (and more superficially) through the material than the mathematicians were prepared to do.

Teaching with functional understanding as a goal carries the responsibility of leaving open the possibility of future refinement or revision of the learner’s concept as and when they progress further. This means that the instructor should have a good grasp of the concept as mathematicians understand and use it. Sadly, many studies have shown that teachers often do not have such understanding, and nor do many writers of school textbooks.

I’ll give you one example of just how bad school textbooks can be. I was visiting some leading math ed specialists in Vancouver a few months ago, and we got to talking about elementary school textbooks. One of the math ed folks explained to me that teachers often explain whole number equations by asking the pupils to imagine objects placed on either side of a balance. Add equal numbers to both sides of an already balanced pairing and the balance is maintained, she explained. The problem then is how do you handle subtraction, including cases where the result is negative? I jumped in with what I thought was an amusing quip. “Well,” I said with a huge grin, “you could always ask the children to imagine helium balloons attached to either side!” At which point my math ed colleagues told me the awful truth. “That’s exactly how many elementary school textbooks do it,” one said. Seeing my incredulity, another added, “They actually have diagrams with colored helium balloons gaily floating above balances.” “Now you know what we are up against,” chimed in a third. I did indeed.

I suspect that I am not alone among MAA members in my ignorance of what goes on at the elementary school level. My professional interest in mathematics education stretches from graduate level down to the top end of the middle school range, with my level of experience and expertise decreasing as I follow that path. Sure, I can see how the helium balloon metaphor can work for the immediate task in hand of explaining how subtraction is the opposite of addition. But talk about a brittle metaphor! It not only breaks down at the very next step, it actually establishes a mental concept that simply has to be unlearned. This is surely a perfect example of using a metaphor that is not consistent with the true concept, and hence very definitely does not lead to anything that can be called conceptual understanding.

A request

As regular readers probably know, I am a mathematician, not a professional in the field of mathematics education. I know many mathematicians, but far fewer math ed specialists. But I am interested in issues of mathematics education, and I have long felt that mathematicians have something to contribute to the field of mathematics education. (Getting rid of those floating helium balloons would be a valuable first step! Stopping teachers saying that multiplication is repeated addition would be a good second.) In fact, is strikes me as surprising that having mathematicians part of the math ed community was for long not a widely accepted no-brainer, but thankfully that now appears to be history. In any event, the above was written from my perspective as a mathematician, and I would be surprised if I have said anything that has not been put through the math ed wringer many times. Accordingly, I would be interested to receive references to work that has been done in the area.

Devlin’s Angle is updated at the beginning of each month.

Mathematician Keith Devlin (email: devlin@csli.stanford.edu) is the Executive Director of the Center for the Study of Language and Information at Stanford University and The Math Guy on NPR’s Weekend Edition. Devlin’s most recent book, Solving Crimes with Mathematics: THE NUMBERS BEHIND NUMB3RS, is the companion book to the hit television crime series NUMB3RS, and is co-written with Professor Gary Lorden of Caltech, the lead mathematics adviser on the series. It is published this month by Plume.

OCTOBER 2007

Kinds of math

Small children learn to understand and produce the language they hear spoken around them rapidly and with no conscious effort, but it takes a lengthy period of struggle to learn to read and write that same language. Yet the written language is merely a symbolic representation on paper (or some other medium) of the structure they hear and speak.

Do you see anything in that last sentence that strikes you as perhaps wrong? I do. It’s that word “merely”. If the written form of language were merely a symbolic representation of the language, it should not be so hard to learn it—so hard that many people never achieve mastery. Spoken language is a system that evolved with our species, over a three million year period culminating, we think, about 100,000 years ago, and to a great extent is characteristic of Homo sapiens. Written language, on the other hand, is a system that our ancestors invented some time around 10,000 B.C. From a cognitive standpoint, written language and spoken language are clearly very different processes.

I believe the same holds for mathematics, at least the parts of mathematics that relate directly to, and indeed are abstracted directly from, the real world in which we live (specifically number, elementary arithmetic, and basic ideas of geometry and trigonometry).

Studies have demonstrated repeatedly that when people find themselves in a situation where they need basic math skills in their everyday lives, they pick them up fairly quickly, and rapidly become fluent.

In one such study, carried out in the early 1990s, three researchers, Terezinha Nunes of the University of London, England, and Analucia Dias Schliemann and David William Carraher of the Federal University of Pernambuco in Recife, Brazil went out into the street markets of Recife with a tape recorder, posing as ordinary market shoppers. Their target subjects were young children aged between 8 and 14 years of age who were looking after their parents’ stalls while the latter were away. At each stall, the researchers presented the young stallholders with transactions designed to test various arithmetical skills.

Working entirely in their heads, with no paper and pencil, let alone a hand calculator, the young children got the correct answer 98% of the time. But posing as customers was just the first stage of the study Nunes and her colleagues carried out. About a week after they had “tested” the children at their stalls, they visited the subjects in their homes and asked each of them to take a pencil-and-paper test that included exactly the same arithmetic problems that had been presented to them in the context of purchases the week before. The investigators took pains to give this second test in as non-threatening a way as possible. It included both straightforward arithmetic questions presented in written form and verbally presented word problems in the form of sales transactions of the same kind the children carried out at their stalls. The subjects were provided with paper and pencil, and were asked to write their answer and whatever working they wished to put down. They were also asked to speak their reasoning aloud as they went along.

Although the children’s arithmetic was practically faultless when they were at their market stalls (just over 98% correct), they averaged only 74% when presented with market-stall word problems requiring the same arithmetic, and a staggeringly low 37% when the same problems were presented to them in the form of a straightforward symbolic arithmetic test.

The researchers noted that the methods the children used—to great effect—in the street-market were not the ones they had been taught (and were still being taught) in school. Rather, in the market they applied methods they had picked up working alongside their parents and friends. Clearly, “street mathematics,” as Nunes and her colleagues called the mental activity they had observed in the marketplace, was quite different from the symbolic symbol system the children encountered in school.

If you want to see details of the methods the children used in the market, and examine the mistakes they made when trying to carry out paper-and-pencil calculations, see the book Street Mathematics and School Mathematics (Learning in Doing: Social, Cognitive and Computational Perspectives) that Nunes and her colleagues wrote about their study.

A description of a similar kind of study carried out in the U.S., this time of price-conscious, adult supermarket shoppers, with similar results, was given by Jean Lave in her book Cognition in Practice: Mind, Mathematics and Culture in Everyday Life (Learning in Doing).

I summarized both studies in my more recent book The Math Instinct.

While we do not yet understand how the human brain does mathematics, either mentally in a real-world environment such as a street market or a supermarket, or in a symbolic fashion using paper and pencil, it seems pretty clear that the two activities are at least as different from each other as are written and spoken language. Written, symbolic mathematics is not “merely” a physically represented version of the mental activity Nunes et al dubbed “street mathematics”.

While modern technology means that a mastery of accurate mental arithmetic skills is nothing like as important today as it used to be, it is generally accepted that a good understanding of number and quantity—what is often called numeracy or quantitative literacy—is absolutely crucial for an individual to be a properly functioning member of present-day society. Recognition of this fact has led to the production of a number of textbooks designed to teach people this important skill.

But wait a minute. Doesn’t something strike you as odd about that development? We don’t use books to teach young children to understand and speak their native language—a Catch 22 challenge if ever there were one; rather, we allow them to pick it up in the environment in which they are exposed to it. Nor do we teach people to read and write musical notation in order for them to enjoy music, to sing, to play a musical instrument, or even to create music; instead, we expose them to music and let them develop singing and playing skill by doing. Why then should be believe for one minute that providing a child with a math textbook will lead to numeracy—to their becoming competent at what I prefer to call “everyday math”?

In fact, I don’t think we do believe that such an approach will work. (Of course, given the variation among people, pretty well any approach is likely to work for some, but the studies by Nunes et al, by Lave, and by others show that all but a tiny minority of individuals become proficient at street mathematics when put in a real-world environment where it is important to them and in which they are exposed to it.) Rather, we write books because that is the dominant technology for recording mathematical knowledge and disseminating it widely. Indeed, until very recently it was our only technology for those purposes.

The textbook approach worked (for many people) in the days when there was sufficient motivation for (many) people to put in the enormous effort required to make it work – as evidenced by the huge effect Leonardo’s book Liber abaci had on western civilization after it appeared in 1202. But it patently does not work in today’s western societies.

And I am leaving aside the question of how we measure whether an individual has achieved the desired level of skill in everyday math. If the evaluation method is to give them a written test, then the child stallholders in Recife would be classified as innumerate, which patently they were not!

As I see it, today, technology and an increased understanding of how people learn provide us with a number of alternatives for teaching and evaluating mastery of everyday math, some computer-based, others focused on physical activities, some making use of both. But examining those alternatives is not the purpose of this essay. I’ll address that exciting future in a later column. Rather, my present point is that we need to recognize the fundamental fact that written, symbolic mathematics is not “merely” a written version of the mental activity I am calling “everyday math.” (Not that I am the first to use that term, nor by any means the only one to use it.) Indeed, from a cognitive standpoint, I don’t think symbolic math is a variant of everyday math at all; I believe it is a very different mental activity. (I have lived long enough to regret my telling generations of college-level students that mathematics is just “formalized common sense”. Everyday math is, but symbolic math is most definitely not.)

Such recognition does not imply that symbolic mathematics is not important. Heavens, our present society depends on it in spades! Our very survival requires a steady supply of individuals with differing degrees of mastery of symbolic math, all the way up to fully-fledged expert. But by conflating two very different kinds of mental activity under the common term “(basic) math”, and tacitly thinking of one as just a written version of the other, I believe we shoot ourselves in both feet when it comes to teaching either kind.

Devlin’s Angle is updated at the beginning of each month.

Mathematician Keith Devlin (email: devlin@csli.stanford.edu) is the Executive Director of the Center for the Study of Language and Information at Stanford University and The Math Guy on NPR’s Weekend Edition. Devlin’s most recent book, Solving Crimes with Mathematics: THE NUMBERS BEHIND NUMB3RS, is the companion book to the hit television crime series NUMB3RS, and is co-written with Professor Gary Lorden of Caltech, the lead mathematics adviser on the series. It was published last month by Plume.

NOVEMBER 2007

The smallest computer in the world

Long before there were iPod Nanos and laptops, in fact, long before before Bill Gates was even born, a British mathematician proved that it was possible to build computing machines that could be programmed to carry out any calculation that could ever arise. The mathematician was Alan Turing, and the theoretical device he invented in the 1930s is nowadays called a Turing machine. (There is not just one Turing machine; rather they are an entire class of hypothetical computing devices. The Wikipedia entry at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Turing_machine provides a good introduction for anyone not familiar with the concept.)

The second world war gave Turing an opportunity to put his theory into practice, and he spent the war years at the British secret code breaking facility in Bletchley Park, building the real computer that was used to break the German Enigma code, a major turning point in the war.

The computer built at Bletchley Park, like all computers since, is much more complicated than Turing’s theoretical machine. In principle you could build a physical Turing machine, and in fact several people have done so, but they are not useful; it could take tens or hundreds of years to program them to carry out useful calculations, and for some problems even longer to find the answer. They may be simple, but they are not practical. Their importance is that they help us understand what computation is and how it works. (For instance, the security of your credit card number when you order something online depends crucially on mathematics involving Turing machines.)

The idea of building machines to do arithmetic (in particular) is almost as old as mathematics itself. The earliest attempts, such as piles of pebbles or the abacus, were not really carrying out the mathematical computation, they simply provided a convenient way to store numbers for the human operator who actually did the math. Blaise Pascal (1623 – 1662) was one of the first people to design and build a machine that really did carry out calculations, called the Pascaline. Charles Babbage (1791 – 1871) is another famous name in the history of designing calculating machines. But all of the early attempts focused on designing machines to perform particular calculations or particular kinds of calculations. No one thought of building a machine that could carry out any computation.

Part of the reason is that it was not until the 1930s that anyone had tried to specify precisely exactly what is meant by “a computation.” Turing invented his “Turing machine” concept in order to provide a precise definition: a function from numbers to numbers (say) is declared to be “computable” if and only if it can be calculated by some Turing machine.

At first encounter, this definition seems excessively narrow. Turing machines are extremely simple computing devices. What about functions that can be computed, but only by using a machine that is more complicated than a Turing machine? Well, there’s a funny thing that happens at this point. Neither in Turing’s time nor at any time since then has anyone produced a single example of a function that is obviously (or provably) computable (by some device or other) yet cannot be computed on a Turing machine. Moreover, around the same time as Turing was doing his work, a number of other mathematicians (among them Kurt Godel, Stephen Kleene, and Alonzo Church) formulated alternative formal definitions of “computable function,” and all turned out to be completely equivalent to Turing’s notion. Thus, a consensus was quickly formed in the mathematical community that Turing’s definition of computable really does capture our more intuitive notion of what it means to be “computable.” This consensus, which remains to this day, is called the Church-Turing Thesis. It replaces an intuitive notion with a precisely defined mathematical one.

One important result that Turing proved about his new concept was that it was not necessary to specify a particular Turing machine for each given computation. It was possible to build what he called a “universal Turing machine,” that could interpret a “program” fed into it as data in order to calculate any computable function it was presented with. Today we are of course familiar with the idea that computers are generally programmable, doing Word processing one minute, mathematics the next, and stealing songs a third. But back at the time of Turing’s work, this was a novel idea, albeit only a theoretical one at the time.

One fascinating question about universal Turing machines is just how simple can a universal Turing machine be (and still be capable of carrying out any possible computation)? Some work was done on this in the 1950s and 60s, and it was shown that a Turing machine that has just two internal states and computes on just two symbols cannot be universal. (Real computers today work in binary, with just two symbols, but have a large number of possible internal states.) The computer science pioneer Marvin Minsky at MIT constructed a universal Turing machine with 7 states, computing on 4 symbols.

Then, in the 1990s, mathematician Stephen Wolfram, perhaps best known as the developer of the software program Mathematica, managed to construct a universal Turing machine with two states that computes on 5 symbols. He also proposed a possible candidate for an even simpler one, one that would be the simplest possible universal Turing machine. Wolfram’s machine has just two different internal states and carries out all computations on just three symbols. It is known as Wolfram 2,3.

Wolfram had reason to believe that his computer was indeed able to perform any possible computation, but was not able to prove it. He described the problem in his 2002 book A New Kind of Science, and that led to various attempts to find a proof, but no one succeeded. Earlier this year, Wolfram offered a prize of $25,000 for the first person to solve it.

Now, just a few months later, a 20-year-old university student in Birmingham, England, Alex Smith, has found a solution. His proof, which is available on the Web, occupies over 50 pages of mathematical reasoning.

Alex is the oldest of three children. Both his parents are lecturers at the University of Birmingham, where he is an undergraduate in Electronic, Electrical and Computer Engineering. He started using computers when he was six years old, and knows around 20 programming languages.

You can find a PDF file of Smith’s proof, plus a lot more detail on Wolfram’s problem, on the Wolfram website at www.wolframscience.com/prizes/tm23/.

Devlin’s Angle is updated at the beginning of each month.

Mathematician Keith Devlin (email: devlin@csli.stanford.edu) is the Executive Director of the Center for the Study of Language and Information at Stanford University and The Math Guy on NPR’s Weekend Edition. Devlin’s most recent book, Solving Crimes with Mathematics: THE NUMBERS BEHIND NUMB3RS, is the companion book to the hit television crime series NUMB3RS, and is co-written with Professor Gary Lorden of Caltech, the lead mathematics adviser on the series. It was published in September by Plume.

DECEMBER 2007

Predicting mathematical ability

Is there any way to predict whether a 3- or 4-year-old pre-schooler will do reasonably well in mathematics when he or she goes to school? Recent research by the psychologist Daniela O’Neill of the University of Waterloo in Canada suggests that there is. What many people will find surprising is that early ability in arithmetic is not a predictor—or at least not as good a predictor as the one O’Neill found: narrative skill. That’s right, the ability to tell a story. The more sophisticated the pre-schooler’s story-telling ability is, the more likely that child is to do well at mathematics two years later.

O’Neill’s result was reported in Science News Online on November 10, 2007 (www.sciencenews.org/articles/ 20071110/mathtrek.asp).

A particularly satisfying aspect of this result from a very personal perspective is that it confirms a prediction I made several years ago. In my book The Math Gene, I provided a natural selection mechanism whereby human beings developed the ability to do mathematics, and the hypothesis O’Neill has confirmed came from that thesis.

The argument I present in The Math Gene for the evolution of mathematical ability is fairly lengthy, which is why it required an entire book to present. Part of the reason for the argument’s complexity is that mathematics is a very recent phenomenon in evolutionary terms. Numbers are a mere 10,000 years old, and recognizable symbolic mathematics goes back only 3,000 years or so. Thus, doing mathematics must comprise making use of mental capacities that pre-date mathematics by tens or hundreds of thousands of years, capacities that found their ways into the human gene pool because they provided our early ancestors with survival advantages—being good at math not being one of them back then! In my book, I spelled out those abilities and explained how and why they got into the gene pool.

Today, we have so much concrete evidence for many of the individual evolutionary advances that led to Homo sapiens and on to modern Man, that the account I gave has considerable support and is fairly tightly constrained. Still, like many evolutionary accounts, perforce it remains a hypothesis. In such a situation, confirmation must be sought by testing any predictions that follow from the hypothesis.

One of the key cognitive abilities that, according to my account, is utilized in doing mathematics is the ability to follow and tell a story. (In the book, I tried to express this in a memorable way by commenting that “a mathematician is someone who approaches mathematics as a soap opera.”)