JANUARY 2003

Dear President Bush

In early December, I received the following email message.

Keith,

Greetings.

This just in from Washington…

From: “George W. Bush” [address restricted]

To: “John Brockman” [address restricted]

Subject: Science Advisor

Date: Sat, 7 December 2002

Dear John,

I appreciate your taking the time to recommend the appointment of Keith Devlin to be my next science advisor and I am pleased to hear of his interest in the position.

I am impressed with the resume of Dr. Devlin which you sent earlier. Could you please ask him to prepare a memo which answers the following question:

“What are the pressing scientific issues for the nation and the world, and what is your advice on how I can begin to deal with them?”

In addition to obvious issues that have dominated the headlines during my first two years in office, I would hope to hear about less obvious scientific issues as well.

I need the memo by the end of December.

Thank you for your help.

Sincerely,

GWB

I smelled a rat long before I got to the end. Sure enough, the message continued:

I wish the above was really an email from President Bush. It is not. It’s the set-up for this year’s Edge Annual Question – 2003, and because this event receives wide attention from the scientific community and the global press, the responses it evokes just might have the same effect as a memo to the President … that is, if you stick to science and to those scientific areas where you have expertise.

I am asking members of the Edge community to take this project seriously as a public service, to work together to create a document that can be widely disseminated to begin a public discussion about the important scientific issues before us.

In case you haven’t come across it, The Edge is an on-line scientists discussion group organized by writer and literary agent John Brockman. Membership of the Edge Community is largely restricted to practicing scientists who have published successful science and science-related books for a general audience. The intention is to provide an ongoing debate of the current leading edge of science in a form that a lay audience can follow. By making writing ability a criterion for contributors, Brockman has clearly excluded from this particular forum a great many leading scientists. But the gain is that The Edge is consistently one of the best places to go to find accessible, stimulating discussions about the latest results and trends in science and technology.

Starting three years ago, The Edge has kicked off each new year with an open-to-all-members discussion about a specific topic—”the Edge Question”. The spoof email I and all other Edge members received gave us this year’s assignment.

So what would you have written? If you are, like me, a mathematician, you almost certainly have a good science general education under your belt, and you probably read Scientific American and one or two other science magazines fairly regularly, but that hardly qualifies us as Presidential Science Advisors. Since I always take The Edge Question seriously, I wondered for a while if I should perhaps simply opt out this year. But then it struck me. Now more than at any time in history, in addition to a Science Advisor, the President needs a “Quantitative Data Advisor”. Here is what I wrote:

Mr President,

I am pleased to learn that I am being considered as your next Science Advisor. Unfortunately, as a mathematician, I do not feel sufficiently well qualified for that position. I do, however, feel there is a clear and demonstrated need for someone on your team to offer advice on interpreting quantitative data, particularly when it comes to risk assessment. I would like to suggest that you create such a position, and I would be pleased to be considered for it.

For well understood evolutionary reasons, we humans are notoriously poor at assessing risks in a modern society. A single dramatic incident or one frightening picture in a newspaper can create a totally unrealistic impression. Let me give you one example I know to be dear to your heart. The tragic criminal acts of September 11, 2001, have left none of us unchanged. We are, I am sure, all agreed that we should do all we can to prevent a repetition.

Strengthening cockpit doors so that no one can force an entrance, as you have done, will surely prevent any more planes being flown into buildings. (El Al has had such doors for many years, and no unauthorized person has ever gained access to the cockpit.)

Thus, the remaining risk is of a plane being blown up either by suicide terrorists on board, by a bomb smuggled into luggage, or by sabotage prior to take-off. In any such case, the likelihood of significant loss of life to people on the ground is extremely low. So low that we can ignore it. The pilot of a plane that has been damaged while in the air will almost certainly be able to direct the plane away from any urban areas, and the odds that any wreckage from a plane that explodes catastrophically in mid-air are overwhelmingly that it will not land on a populated region.

I know that what I say might sound cavalier or foolhardy or uncaring. The hard facts the numbers present often fly in the face of our emotional responses and our fears. But the fact is, we have limited resources, and we need to decide where best to deploy them. This is why you need someone to help you assess risk.

That leaves the threat to the plane and the people on board. Let me try to put that risk into some perspective. For a single individual faced with a choice of driving a car or flying, how do the dangers of the two kinds of transport compare in the post September 11 world? We know the answer, thanks to a calculation carried out recently at the University of Michigan Transportation Research Institute. In order for commercial air travel to be as risky (in terms of loss of life) as driving a car on a major road, there would have to be a September 11 style incident roughly once every month, throughout the year.

Let me stress that this figure is not based on comparing apples and oranges, as some previous airline safety studies have done. By being based on the lengths of journeys, those previous studies made airline travel appear safer than it really is. The figure I have given you is based on the computed risk to a single individual. It compares the risks we face, for the journey we are about to take, when any one of us decides whether to board a plane or step into our car. In other words, “How likely am I to die on this trip?”

The answer, as the figures show—and let me stress that the calculation takes full account of the September 11, 2001 attack—is that there would have to be such an attack once every month before air travel offers the same kind of risk as car travel.

In short, Mr. President, most of the current effort being put into increasing airline safety is a waste of valuable resources. In a world where fanatical individuals are willing to give their own lives to achieve their goals, we can never be 100% safe. What we should do, is direct our resources in the most efficient manner possible.

In that connection, if you have not already done so, I recommend you see the movie The Sum of All Fears, where terrorists smuggle an atomic bomb into the United States in a shipping crate and detonate it in downtown Baltimore. Leaving aside the details of the plot, the risk portrayed in that film is real, and one where we would be advised (and I would so advise you) to put the resources we are currently squandering on airline security.

That is why you need expert assistance when it comes to interpreting the masses of numerical data that surround us, and putting those numbers into simple forms that ordinary human beings, including Presidents, can appreciate.

Numerically yours,

Keith Devlin

I began my “letter” with the mindset Brockman asked for, namely suspending disbelief and pretending I really was writing a letter to President Bush. By the time I had finished, I wished I really was. Not because I see myself hanging around the West Wing—although I’m sure it would be fun. (“No, Mr. Jennings, I have no current plans in that direction; however, if my country … “) No, what happened was that as I wrote, I realized just how much the President really does need such advice.

Sure, he is not short of advice, coming from many sources. But that is just the problem. There’s too much of the stuff. Even summaries are at best of limited use. Carefully crafted summary reports, with columns of figures, spreadsheets, and graphs appended at the end, take time to digest and appreciate. Time the President, or the CEO of any company, simply does not have. Instead, he has to rely on a small group of trusted colleagues to interpret that data and put it in a form he can appreciate and make use of. And that means it has to be presented in simple everyday terms that can be understood and appreciated on a human level, without any special effort.

Mathematics and statistics, like the natural sciences, draw their strength from being abstract. They are powerful tools, and no President or CEO should ignore them. But if I had the fate of even one person in my hands, let alone a large part of the world, I would want more than percentages. I would want those numbers put into human terms. One question I would want to know the answer to before making any decision is “If I were in that position—if I were that airline traveler, policeman, army sergeant, school-teacher, or whatever—what would it mean to me?” In other words, I’d want to see the individual human face of the issue.

That means that among those who advise the President, and whom he trusts, there should be someone able to take quantitative data, perhaps masses of the stuff, and present it to him in simple human terms—terms that mean something to a human being. Many of his decisions so far make me suspect he does not currently receive such assistance.

NOTES:

To see all the contributions to this year’s Edge Question, direct your browser to take you to The Edge.

The full report on airline safety that I refer to is Flying and Driving After the September 11 Attacks, by Michael Sivak and Michael J. Flannagan, American Scientist, Vol 91, No. 1, January-February 2003, pp.6-8.

Devlin’s Angle is updated at the beginning of each month.

Mathematician Keith Devlin ( devlin@csli.stanford.edu) is the Executive Director of the Center for the Study of Language and Information at Stanford University and “The Math Guy” on NPR’s Weekend Edition. His book The Millennium Problems: The Seven Greatest Unsolved Mathematical Puzzles of Our Time was published last fall by Basic Books.

FEBRUARY 2003

Squaring the circle

Mathematicians who speak on the radio or write for a local or national newspaper generally find their brief moment of fame results in a small postbag of letters from individuals who claim to have solved some major mathematical problem. In my own experience, Fermat’s Last Theorem and Squaring the Circle easily top the list. Having just completed a small blitz of media appearances surrounding the publication last fall of my new book The Millennium Problems, I have received a number of Fermat proofs and circle squaring attempts. (Never mind that neither of these is a Millennium Problem.)

Word certainly seems to have gotten around that someone claimed to have proved Fermat’s Last Theorem a few years ago, though few of my correspondents at least could name the solver as Princeton’s Andrew Wiles or the year as 1994. (Please don’t write and say it was 1993. That was the year of the initial announcement of the result, but Wiles subsequently withdrew his claim after a major flaw was found in the proof. He corrected it the following year, and hence 1994 is the year it was solved.) Unfortunately for the poor mail carrier at my university, however, word also got around that the 1994 proof is long and complicated, and not everyone heard the news that the mathematical community did eventually sign off on the correctness of Wiles’ 1994 proof. That left open the door for an enthusiastic amateur to seek a proof using elementary (i.e., high school) methods.

I long ago stopped responding. As someone who loves mathematics, I do not want to prevent others from gaining similar enjoyment from the field, and if an individual gains pleasure from battling away trying to find an elementary proof of Fermat’s Last Theorem or any other result, then they have my blessing. Their enjoyment in mathematics is surely not unlike mine. But my earlier approach—twenty years ago, I should add, when I first forayed into the pages of national newspapers—of writing back with what I thought was a helpful response, soon had to be abandoned. Finding an error in the proposed proof and gently pointing it out to the correspondent invariably led to a small deluge of attempted corrections, or sometimes to indignant letters insisting that what I had suggested was a mistake was nothing of the kind. Eventually, I learned that I could not win. Sooner or later I would have to stop responding, and at that point I would unavoidably come across as aloof, a member of a cabal-like Establishment that would do anything to prevent a genius outsider from gaining entrance to the Mathematical Club.

With Fermat’s Last Theorem, there is of course always a tiny chance that someone does find a proof simpler than the one Wiles came up with—although it will surely involve more than a variation on the classical proof of Pythagoras’ Theorem, which is the favored approach of most amateurs who write to me. With the ancient Greek challenge of Squaring the Circle, however, I can be completely certain that any proposed solution is incorrect. Lindemann’s 1882 proof that pi is transcendental implied that it is impossible to construct a square with area equal to that of a given circle using only a ruler (more precisely, an unmarked straightedge) and compass (of a type which loses its separation when taken off the paper). Sadly, word of Lindemann’s result does not seem to have gotten around sufficiently well.

I added in those two parenthetical comments when I stated the Squaring the Circle problem just now because many people who send in proofs do not realize that “Squaring the Circle” is a Greek intellectual game with highly constrained rules. Relax those rules—for instance by allowing the ruler to have two fixed marks on its straightedge—and it is indeed possible to square a circle. At least, I seem to recall reading that somewhere. I have to confess that except for a brief period at high school (in the US it would have been middle school) when I first encountered ruler-and-compass constructions and found them an enjoyable challenge, I have never had much enthusiasm for the topic. It always struck me as so very artificial and contrived. Which it is.

“Useless” topics like ruler and compass constructions also tend to help perpetuate the myth that mathematicians do not care about applications of the subject. True, I know a few who do not—or at least that is what they say—but my sense is they are very much a minority. What may well be the case is that many mathematicians—at least those who work in universities—are not primarily motivated by applications. But that is probably true for the majority of scientists and engineers as well. Being truly successful in any field requires such dedication that it can only come from a love of the discipline itself, not the applications. In mathematics, this is particularly acute, since applications of a new discovery or technique often come many years later, perhaps after the individuals who did the mathematics are long dead. But being motivated by the internal mechanics of a discipline does not mean a lack of interest in what others can do with it. On the contrary, mathematicians are like anyone else: we are usually fascinated to see what our efforts lead to.

Much if the blame for the “mathematicians don’t care about applications” myth comes, I believe, from the remarks made by G. H. Hardy in his book A Mathematician’s Apology.Hardy’s views reflect the snobbery prevalent at Cambridge University (and to a lesser extent elsewhere in England) in the early decades of the twentieth century, when academics went to great lengths to portray themselves as “gentlemen” (there were hardly any women there at the time), whose intellectual abilities put them above having to worry about the issues of the real world. I have no idea how such views appeared to outsiders at the time, but they seem completely out of place today. It’s time that myth was put to rest once and for all.

Of course, it can sometimes be very difficult providing an answer to the question “What is this good for?” I faced precisely that question many times when I was being interviewed about The Millennium Problems. For some of the problems, I was able to give an answer of sorts. For example, a proof of the Riemann Hypothesis might well have implications for Internet security. The RSA algorithm, the current industry standard, depends on the difficulty of factoring large numbers into prime factors, and a proof of the Riemann Hypothesis would likely have an impact on that issue. But it has to be added that it’s not the solution of the problem per se that would make the difference. Number theorists have been investigating the consequences of the hypothesis for years. Rather, it’s the new methods that we assume would be required to solve the problem that are likely to impact the RSA method.

The fact is, it’s virtually impossible to predict how and when a major advance in mathematics will affect the lives of everyday people. The Millennium Problems lie at the very pinnacles of mathematical mountains. They are the Mount Everests of mathematics. The air is thin up there, and only the most able should attempt to scale those peaks. But their very height is what makes their potential impact so great. As every climber and skier knows full well, if you make a sudden move at the top of a mountain, the small movement in the snowpack that results can lead to a major avalanche thousands of feet down below. It’s hard to predict exactly what direction the snow will move, and where the main force of the avalanche will hit when it reaches the bottom. But for the people down at sea level, the impact can be huge. Solving a Millennium Problem would cause a ripple effect all the way down the mountain of mathematics. We can’t know in advance where the effects will be felt first. But we can be pretty sure they will be big.

Finally, Scrabble players are likely to enjoy the following “Squaring the Circle” puzzle I came across some years ago. Fill in the blanks in the following square so that every row and column is a word of the English language. This one can be solved. In fact there are several solutions.

Devlin’s Angle is updated at the beginning of each month.

Mathematician Keith Devlin ( devlin@csli.stanford.edu) is the Executive Director of the Center for the Study of Language and Information at Stanford University and “The Math Guy” on NPR’s Weekend Edition. His book The Millennium Problems: The Seven Greatest Unsolved Mathematical Puzzles of Our Time was published last fall by Basic Books.

MARCH 2003

The Forgotten Revolution

We mathematicians are used to the fact that our subject is widely misunderstood, perhaps more than any other subject (except perhaps linguistics). Misunderstandings come on several levels.

One misunderstanding is that the subject has little relevance to ordinary life. Many people are simply unaware that many of the trappings of the present-day world depend on mathematics in a fundamental way. When we travel by car, train, or airplane, we enter a world that depends on mathematics. When we pick up a telephone, watch television, or go to a movie; when we listen to music on a CD, log on to the Internet, or cook our meal in a microwave oven, we are using the products of mathematics. When we go into hospital, take out insurance, or check the weather forecast, we are reliant on mathematics. Without advanced mathematics, none of these technologies and conveniences would exist.

Another misunderstanding is that, to most people, mathematics is just numbers and arithmetic. In fact, numbers and arithmetic are only a very small part of the subject. To those of us in the business, the phrase that best describes the subject is “the science of patterns,” a definition that only describes the subject properly when accompanied by a discussion of what is meant by “pattern” in this context.

It’s not hard to find the reasons for these common misconceptions. Most of the mathematics that underpins present-day science and technology is at most three or four hundred years old, in many cases less than a century old. Yet the typical high school curriculum covers mathematics that is for the most part at least five hundred and in many cases over two thousand years old. It’s as if our literature courses gave students Homer and Chaucer but never mentioned Shakespeare, Dickens, or Proust.

Still another common misconception is that mathematics is mainly about performing calculations or manipulating symbolic expressions to solve problems. But this misconception is different. Whereas a scientist or engineer—indeed anyone who has studied any mathematics at the university level—will not harbor the first two misconceptions, possibly only pure mathematicians are likely to be free of this third misconception. The reason is that until 150 years ago, mathematicians themselves viewed the subject the same way. Although they had long ago expanded the realm of objects they studied beyond numbers and algebraic symbols for numbers, they still regarded mathematics as primarily about calculation.

In the middle of the nineteenth century, however, a revolution took place. One of its epicenters was the small university town of Goettingen in Germany, where the local revolutionary leaders were the mathematicians Lejeune Dirichlet, Richard Dedekind, and Bernhard Riemann. In their new conception of the subject, the primary focus was not performing a calculation or computing an answer, but formulating and understanding abstract concepts and relationships—a shift in emphasis from doing to understanding. Within a generation, this revolution would completely change the way pure mathematicians thought of their subject. Nevertheless, it was an extremely quiet revolution that was recognized only when it was all over. It is not even clear that the leaders knew they were spearheading a major change.

The 1850s revolution did, after a fashion, eventually find its way into school classrooms in the form of the 1960s “New Math” movement. Unfortunately, by the time the message had made its way from the mathematics departments of the leading universities into the schools, it had been badly garbled. To mathematicians before and after 1850, both calculation and understanding had always been important. The 1850 revolution merely shifted the emphasis as to which of the two the subject was really about and which was the supporting skill. Unfortunately, the message that reached the nation’s school teachers in the 60s was often, “Forget calculation skill, just concentrate on concepts.” This ludicrous and ultimately disastrous strategy led the satirist Tom Lehrer to quip, in his song New Math, “It’s the method that’s important, never mind if you don’t get the right answer.” (Lehrer, by the way, is a mathematician, so he knew what the initiators of the change had intended.) After a few sorry years, “New Math” (which was already over a hundred years old) was dropped from the syllabus.

For the Goettingen revolutionaries, mathematics was about “Thinking in concepts” ( Denken in Begriffen). Mathematical objects were no longer thought of as given primarily by formulas, but rather as carriers of conceptual properties. Proving was no longer a matter of transforming terms in accordance with rules, but a process of logical deduction from concepts.

Among the new concepts that the revolution embraced are many that are familiar to today’s university mathematics student; function, for instance. Prior to Dirichlet, mathematicians were used to the fact that a formula such as y = x2 + 3x – 5 specifies a rule that produces a new number (y) from any given number (x). Dirichlet said forget the formula and concentrate on what the function does. A function, according to Dirichlet, is any rule that produces new numbers from old. The rule does not have to be specified by an algebraic formula. In fact, there’s no reason to restrict your attention to numbers. A function can be any rule that takes objects of one kind and produces new objects from them.

Mathematicians began to study the properties of abstract functions, specified not by some formula but by their behavior. For example, does the function have the property that when you present it with different starting values it always produces different answers? (The property called bijectivity.)

This approach was particularly fruitful in the development of real analysis, where mathematicians studied the properties of continuity and differentiability of functions as abstract concepts in their own right. In France, Augustin Cauchy developed his famous epsilon-delta definitions of continuity and differentiability – the “epsilontics” that to this day cost each new generation of mathematics students so much effort to master. Cauchy’s contributions, in particular, indicated a new willingness of mathematicians to come to grips with the concept of infinity. Riemann spoke of their having reached “a turning point in the conception of the infinite.”

In 1829, Dirichlet deduced the representability by Fourier series of a class of functions defined by concepts. In a similar vein, in the 1850s, Riemann defined a complex function by its property of differentiability, rather than a formula, which he regarded as secondary. Karl Friedrich Gauss’s residue classes were a forerunner of the approach—now standard—whereby a mathematical structure is defined as a set endowed with certain operations, whose behaviors are specified by axioms. Taking his lead from Gauss, Dedekind examined the new concepts of ring, field, and ideal—each of which was defined as a collection of objects endowed with certain operations.

Like most revolutions, this one had its origins long before the main protagonists came on the scene. The Greeks had certainly shown an interest in mathematics as a conceptual endeavor, not just calculation, and in the seventeenth century, Gottfried Leibniz thought deeply about both approaches. But for the most part, until the Goettingen revolution, mathematics remained primarily a collection of procedures for solving problems. To today’s mathematicians, however, brought up entirely with the post-Goettingen conception of mathematics, what in the 19th century was a revolution is simply taken to be what mathematics is. The revolution may have been quiet, and to a large extent forgotten, but it was complete and far reaching. The only remaining question is how long it will take nonmathematicians to catch up.

Devlin’s Angle is updated at the beginning of each month.

Mathematician Keith Devlin ( devlin@csli.stanford.edu) is the Executive Director of the Center for the Study of Language and Information at Stanford University and “The Math Guy” on NPR’s Weekend Edition. Thid column was adapted from his most recent book The Millennium Problems: The Seven Greatest Unsolved Mathematical Puzzles of Our Time,published last fall by Basic Books.

APRIL 2003

The Double Helix

[NOTE: There is no record of the images originally shown in this post. The images shown here have been selected to accord with the original text. KD, September 2023]

Quick, what do you get when you double a helix?

The answer, as everyone knows, is a Nobel Prize. Exactly fifty years ago this month, on April 25, 1953, the molecular biologists James D. Watson and Francis H. C. Crick published their pivotal paper in Nature in which they described the geometric shape of DNA, the molecule of life. The molecule was, they said, in the form of a double helix—two helices that spiral around each other, connected by molecular bonds, to resemble nothing more than a rope ladder that has been repeatedly twisted along its length. Their Nobel Prizewinning discovery opened the door to a new understanding of life in general and genetics in particular, setting humanity on a path that in many quite literal ways would change life forever.

“This structure has novel features which are of considerable biological interest,” they wrote. Well, duh. You’re telling me it does. But does the structure have any mathematical interest? More generally, never mind the double helix, does the single helix offer the mathematician much of interest?

Given the neat way the two intertwined helices in DNA function in terms of genetic reproduction, you might think that the helix had important mathematical properties. But as far as I am aware, there’s relatively little to catch the mathematician’s attention.

The equation of the helix is quite unremarkable. In terms of a single parameter t, the equation is

x = a cos t, y = a sin t, z = b t

This is simply a circular locus in the xy-plane subjected to constant growth in the z-direction.

A deeper characterization of a helix is that it is the unique curve in 3-space for which the ratio of curvature to torsion is a constant, a result known as Lancret’s Theorem.

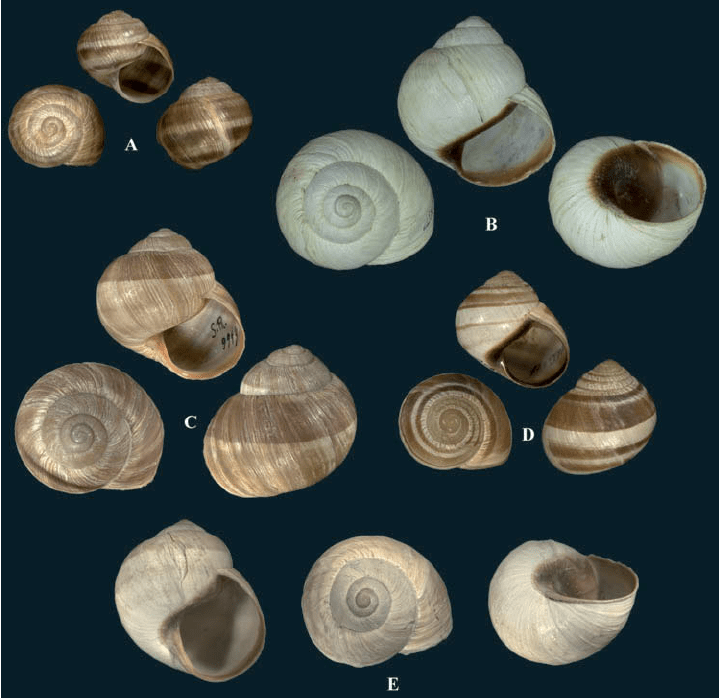

Helices are common in the world around us. Various sea creatures have helical shells, like the ones shown here

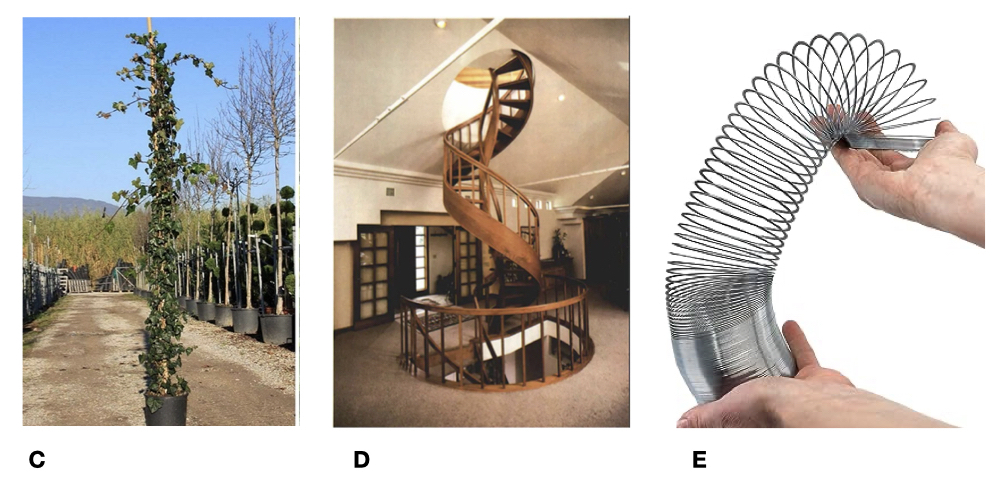

In the natural world (see image below), climbing vines wind around supports to trace out a helix [C]; in the technological world of our own making, spiral staircases [D] lead to higher things; corkscrews, drills, bedsprings, and telephone handset chords are helix-shaped; and the popular Slinky toy [E] shows that the helix is capable of providing amusement for even the most non mathematical among us.

And what kind of a world would it be without the binding capacity the helix provides in the form of various kinds of screws and bolts (image below):

One of the most ingenious uses of a helix was due to the ancient Greek mathematician Archimedes, who was born in Syracuse around 287 BC. Among his many inventions was an elegant device for pumping water uphill for irrigation purposes. Known nowadays as the Archimedes screw, it comprised a long, helix-shaped wooden screw encased in a wooden cylinder. By turning the screw, the water is forced up the tube. The same device was also used to pump water out of the bilges of ships.

But when you look at each of these useful applications, you see that there is no deep mathematics involved. The reason the helix is so useful is that it is the shape you get when you trace out a circle at the same time as you move at a constant rate in the direction perpendicular to the plane of the circle. In other words, the usefulness of the helix comes down to that of the circle.

So where does that leave mathematicians as biologists celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of the discovery that the helix was fundamental to life? Well, if what you are looking for is a mathematical explanation of why nature chose a double helix for DNA, the answer is: on the sidelines. On this occasion, the mathematics of the structure simply does not appear to be significant.

On the other hand, that does not mean that Crick and Watson did not need mathematics to make their discovery. Quite the contrary. Crick’s own work on the x-ray defraction pattern of a helix was a significant step in solving the structure of DNA, which involved significant applications of mathematics (Fourier transforms, Bessel functions, etc.). Based on these theoretical calculations, Watson quickly recognized the helical nature of DNA when he saw one of Rosalind Franklin’s x-ray diffraction patterns. In particular, Watson and Crick looked for parameters that came from the discrete nature of the DNA helices.

In the scientific advances that followed Crick and Watson’s breakthrough, in particular the cracking of the DNA code, mathematics was much more to the fore. But that is another story. In the meantime, I hope I speak for all mathematicians when I wish the double-helix a very happy fiftieth birthday.

NOTE: Jeff Denny of the Department of Mathematics at Mercer University contributed to this month’s column.

Devlin’s Angle is updated at the beginning of each month.

Mathematician Keith Devlin ( devlin@csli.stanford.edu) is the Executive Director of the Center for the Study of Language and Information at Stanford University and “The Math Guy” on NPR’s Weekend Edition. His most recent book is The Millennium Problems: The Seven Greatest Unsolved Mathematical Puzzles of Our Time, published last fall by Basic Books.

MAY 2003

The shame of it

I am sure I am not the only mathematician who has had to hang my head in shame at the sloppy behavior of my colleagues who announce major results that they subsequently have to withdraw when it is discovered that they have made a mistake. We expect high school students to make mistakes on their math homework, but highly paid professionals with math Ph.D.s are surely supposed to be beyond that, aren’t they?

The rot set in 1993, when Andrew Wiles was forced to withdraw his dramatic claim to have proved Fermat’s Last Theorem. His subsequent discovery of a correct proof several months later hardly served to make up for the dreadful example he had set to an entire generation of potential future mathematicians, who followed the “has he, hasn’t he?” activities from their high school math classrooms.

Then, this year, we have the entire mathematical profession admitting that they are not yet sure that Russian mathematician Grigori Perelman’s claimed proof of the Poincare Conjecture is correct or not months after he first posted details on the Internet. Surely, any math teacher can tell in ten minutes whether a solution to a math problem is right or wrong! What are my professional math colleagues playing at? Come on folks, it’s a simple enough question. Is his math right or wrong?

Now we have American mathematician Daniel Goldston and Turkish mathematician Cem Yildirim admitting that their recently claimed major advance on the famous Twin Primes Conjecture has a flaw that they are not yet able to fix. A result that many of the world’s leading mathematicians had already declared to be one of the most significant breakthroughs in number theory in the past fifty years. Can’t all those experts tell whether a solution to a math problem is right or wrong any more? Have standards fallen so low, not only among students but the mathematics professoriate as well?

If you have been nodding in increasing agreement as you read the above paragraphs, then I can draw two fairly confident conclusions about you. First, you don’t know me very well. That’s okay, I’m sure you can get along fine in life not knowing that I harbor a mischievous streak. More worrying though is that you have little understanding of the nature of modern mathematics. That’s worrying because, in an era when a great deal of our science, technology, defense, and medicine are heavily dependent on mathematics, harboring a false, outdated (and dare I say hopelessly idealistic?) view of the subject is positively dangerous—at least if you are a voter, and even more so if you are in a position of authority. (You might, for instance, be led to believe that a missile defense shield with a reliability factor of 95% is worth spending billions of dollars on. No this is not a political comment. It’s a mathematical issue. Think about that other 5% for a moment and ask yourself what 5% of, oh, let’s say 500 incoming missiles would represent. After that, we’re all free to make up our own minds.)

The fact is, during the 20th century, much of mathematics grew so complex that it really can take months of very careful scrutiny by a large number of mathematicians to check whether a purported new result is correct or not. That does reflect on mathematicians to some extent, but in a positive way, not a negative one. Mathematicians have pushed the mathematical envelope to such an extent that the field has gone well beyond problems for which solutions might take up a page or two, and solutions that can be checked in a few hours, or even a few weeks. Those that are familiar with the field know this. That is why Andrew Wiles would have been regarded as one of the greatest mathematicians of our time even if he had not been able to patch up his proof. No one who understood what he had done ever doubted that he had made a major breakthrough. What was in question for a while was whether his new methods really did prove Fermat’s Last Theorem. Whether they did or not, his new methods were sure to lead to many further advances. In fact, from a mathematical point of view, the least significant aspect of his work was whether or not it solved Fermat’s 350 year old riddle. The importance of that particular aspect of what he had (or had not) done was cultural, not mathematical.

The Poincare conjecture goes back to the start of modern topology a hundred years ago. Mathematicians in the 19th century had been able to describe all smooth, two-dimensional surfaces. Henri Poincare tried to do the same thing for three-dimensional analogues of surfaces. In particular, he conjectured that any smooth 3-surface that has no edges, no corkscrew-like twists, and no doughnut-like holes must be topologically equivalent to a 3-sphere. The two-dimensional analogue of this conjecture had been proved by Bernhard Riemann in the mid 19th century. In fact, at first Poincare simply assumed it was true for 3-surfaces as well, but he soon realized that it was not as obvious as he first thought. In recent years, the result has been shown to be true for any surfaces of dimension 4 or more, but the original 3-dimensional case that tripped Poincare up remains unproved.

The problem is regarded as so important that it is one of the seven problems chosen in 2000 by the Clay Mathematics Institute as Millennium Problems, for each of which a $1 million prize is offered for the first person to solve it. (For more details of this competition, see my recent book, details of which are given at the end of this article.) Over the years, several mathematicians have announced solutions to the problem, but on each occasion an error was subsequently found in the solution—although such has been the complexity of the proposed proofs that it generally took several months before everyone agreed the attempt had failed.

Recognizing the difficulty of checking modern mathematical solutions to the most difficult problems, the Clay Insitute will not award the $1 million prize for a solution to any of the Millennium Problems until at least one year has elapsed after the solution has (i) been submitted to a mathematics journal, (ii) survived the refereeing process for publication, and (iii) actually appeared in print for the whole world to scrutinize.

When Wiles proved Fermat’s Last Theorem, he did so by proving a much stronger and far more general result that implied Fermat’s Last Theorem as a corollary. The same is true for Perelman’s clamed proof of the Poincare Conjecture. He says he has managed to prove a very general result known as the “geometrization conjecture”, formulated by mathematician Bill Thurston (now at UC Davis) in the late 1970s. Roughly speaking, this goes part way to providing a complete topological description of all 3-D surfaces by saying that any 3-D surface can be manipulated so that it is made up of pieces each having a nice geometrical form.

In the 1980s, Richard Hamilton (now at Columbia University) suggested that one way to set about proving Thurston’s conjecture was by analogy with the physics of heat flow. The idea was to set up what is called a “Ricci flow” whereby the given surface would morph itself into the form stipulated in the geometrization conjecture. Hamilton used this approach to reprove Riemann’s 19th century result for 2-D surfaces, but was not able to get the method to work for 3-D surfaces. Last November, Perelman posted a message on the Internet claiming he had found a way to make the Ricci flow method work for 3-D surfaces to prove the geometrization conjecture.

Mindful of the ever present possibility of a fatal flaw in his reasoning, Perelman has been careful not to go beyond claiming he thinks he has solved the problem. In addition to posting details of his argument on the Internet for anyone to examine, he has been lecturing about his proposed solution at major universities in the US, again inviting other mathematicians to scrutinize his argument in detail — to try to find a major flaw. As was the case with Wiles’ work Fermat’s Last Theorem, everyone who has looked at Perelman’s work has no doubt that he has made a major breakthrough in the field of topology that will significantly advance the subject. What no one is yet prepared to do is go on record as saying he has proved the Poincare Conjecture.

And so to Goldston and Yildirim’s proof (or not) of a major result related to the Twin Primes Conjecture.

The Twin Primes Conjecture says that there are infinitely many pairs of primes that are just 2 numbers apart: pairs such as 3 and 5, 17 and 19, or 101 and 103. Although computer searches have produced many such pairs, the largest such to date having over 50,000 digits, no one has been able to prove that there are an infinite number of them. Who cares? you might ask. And with some justification. The Twin Primes Conjecture is one of those mathematical riddles that as far as we know has no practical applications, whose fame rests purely on the fact that it is easy to state and understand, has an intriguing name, and has resisted proof for several centuries.

But then, the same can be said of Fermat’s Last Theorem. The lasting significance of Wiles’ proof of that puzzle was that the method he developed to solve the problem has had—and will continue to have—major ramifications throughout number theory. And the same can probably be said of the Goldston-Yildirim result, provided they are able to correct the error. For what they thought they had done was estabish a deep result about how the primes are distributed among the natural numbers.

It has been known for over a century that as you progress up through the natural numbers, the average gap between one prime number p and the next is the natural logarithm of p. (This is known as the Prime Number Theorem.) But this is just an average. By how much can the gap differ from that average?

In 1965, Enrico Bombieri (then at the University of Pisa and now at Princeton) and Harold Davenport (of Cambridge) proved that gaps less than half the average (i.e., less than 0.5 log p) occur infinitely often. In subsequent years, other mathematicians improved on that result, eventually showing that gaps less than 0.25 log p crop up infinitely often. But then things ground to a halt. Until, a few weeks ago, Goldston and Yildirim presented a proof that the fraction could be made as small as you please. That is to say, for any positive fraction k, there are infinitely many primes p such that the gap to the next prime is less than k log p.

This is still well short of the Twin Primes Conjecture, which says that there are infinitely many primes p for which the gap to the next prime is exactly 2. But from a mathematical standpoint, the Goldston-Yildirim result is a major result having many ramifications. At least, it will be if it turns out to be true. In the meantime, everyone who has read the “proof,” including Andrew Granville of the University of Montreal and Kannan Soundarajan of the University of Michigan who uncovered the possibly fatal flaw in the reasoning, is clear that the new work is still an important piece of mathematics.

And there you have it. Three recent claims of major new advances, each of which has highlighted just how hard it can be to check if a modern proof is correct or not. The score so far: one is definitely correct, for one the jury is still out, and for the third the current proof is definitely wrong, and although the authors may be able to patch it up, the experts think this is unlikely.

Shame? Is there anything for mathematicians to be ashamed of, as I jokingly began? Only if it is shameful to push the limits of human mental ability, producing arguments that are so intricate that it can take the world’s best experts weeks or months to decide if they are correct or not. As they say in Silicon Valley, where I live, if you haven’t failed recently, you’re not trying hard enough. No, I am not ashamed. I’m proud to be part of a profession that does not hesitate to tackle the hardest challenges, and does not hesitate to applaud those brave individuals who strive to reach the highest peaks, who stumble just short of the summit, but perhaps discover an entire new mountain range in the process.

NOTE: For details on Perelman’s work on the Poincare Conjecture, click here and here. For details of the Goldston-Yildirim work, click here.

Devlin’s Angle is updated at the beginning of each month.

Mathematician Keith Devlin ( devlin@csli.stanford.edu) is the Executive Director of the Center for the Study of Language and Information at Stanford University and “The Math Guy” on NPR’s Weekend Edition. His most recent book is The Millennium Problems: The Seven Greatest Unsolved Mathematical Puzzles of Our Time, published last fall by Basic Books.

JUNE 2003

When is a proof?

What is a proof? The question has two answers. The right wing (“right-or-wrong”, “rule-of-law”) definition is that a proof is a logically correct argument that establishes the truth of a given statement. The left wing answer (fuzzy, democratic, and human centered) is that a proof is an argument that convinces a typical mathematician of the truth of a given statement.

While valid in an idealistic sense, the right wing definition of a proof has the problem that, except for trivial examples, it is not clear that anyone has ever seen such a thing. The traditional examples of correct proofs that have been presented to students for over two thousand years are the geometric arguments Euclid presents in his classic text Elements, written around 350 B.C. But as Hilbert pointed out in the late 19th century, many of those arguments are logically incorrect. Euclid made repeated use of axioms that he had not stated, without which his arguments are not logically valid.

Well, can we be sure that the post-Hilbert versions of Euclid’s arguments are right wing proofs? Like most mathematicians, I would say yes. On what grounds do I make this assertion? Because those arguments convince me and have convinced all other mathematicians I know. But wait a minute, that’s the left wing definition of proof, not the right wing one.

And there you have the problem. Like right wing policies, for all that it appeals to individuals who crave certitude in life, the right wing definition of mathematical proof is an unrealistic ideal that does not survive the first contact with the real world. (Unless you have an army to impose it with force, an approach that mathematicians have hitherto shied away from.)

Even in the otherwise totally idealistic (and right wing) field of mathematics, the central notion of proof turns out to be decidedly left wing the moment you put it to work. In other words, the only notion of proof that makes real sense in mathematics, and which applies to what mathematicians actually do, is the left wing notion.

So much for “What is a proof?” An argument becomes a proof when the mathematical community agrees it is such. How then about the related question “When is proof?” At what point does the community of mathematicians agree that a purported statement has been proved? When does the argument presented become a proof?

In last month’s column, I looked at three recent examples of mathematical proofs that illustrate this question “When is proof?” They are: Andrew Wiles’ 1993 presentation of a proof of Fermat’s Last Theorem, Russian mathematician Grigori Perelman’s 2002 claim to have “possibly proved” the Poincare Conjecture, and Daniel Goldston and Cem Yildirim’s 2003 announcement of a major advance on the Twin Primes Conjecture. All three are far too long and complicated for anyone to seriously believe these are anything but left-wing proofs.

In Wiles’ case, a major flaw was discovered in his argument within months of his initial announcement, which took him over a year to fix. (His proof is now accepted as being correct.) Perelman has been guarded in his claim, admitting that it will likely take months before the mathematical community will know for sure whether he is right or not. In the case of the Goldston-Yildirim result, they and the rest of the mathematical community were still sipping their celebratory champagne when Andrew Granville of the University of Montreal and Kannan Soundarajan of the University of Michigan discovered a flaw in the new proof, a flaw that is almost certainly fatal.

Subsequent to the publication of my commentary, Granville sent me an email providing some background on what led him and his colleague to discover the error in the Goldston-Yildirim proof. This episode provides an excellent example of the psychology of doing mathematics.

Like everyone else, when they first read through Goldston and Yildirim’s proof, Granville and Soundarajan thought it was correct. The result was dramatic and surprising, but the argument seemed to work. Like any new mathematical result, the proof was a mixture of old and familiar techniques and some new ideas. Because the result was such a major breakthrough, Granville and Soundarajan, like everyone else, looked especially carefully at the new ideas. Everything seemed okay.

Goldston and Yildirim did not claim to have proved the Twin Prime Conjecture, that there are infinitely many pairs of primes just 2 apart (such as 3 and 5 or 11 and 13), but they did claim to have made major progress in that direction, showing that there are infinitely many primes p such that the gap to the next prime is very small. (See last month’s column for a precise statement.)

Granville and Soundarajan took Goldston and Yildirim’s argument and extended it to show that there are infinitely many pairs of primes differing by no more than 12. In Granville’s own words, “We were damn close to twin primes!”

Too close, in fact. Not believing their result, the two decided to look again at Goldston and Yildirim’s core lemmas to see if there was some crucial detail that was being too easily glossed over. It took only a couple of hours to home in on one tiny detail that was not fully explained and which they could not prove. And with the discovery of that one tiny flaw, buried deep in the “tried and tested” part of the argument that everyone had accepted as correct, the entire Goldston and Yildirim result fell apart. It wasn’t that the established procedure was in itself wrong; rather, it did not apply under the new circumstances in which Goldston and Yildirim were using it.

Brian Conrey, the director of the American Institute of Mathematics, which played an instrumental role in the research that led Goldston and Yildirim to develop their argument, has commented on how this incident highlights the psychology of breakthrough in mathematics. Goldston and Yildirim’s core lemmas had a familiar flavor and their conclusions were very believable, so everyone believed them. The expectation was that if there was a mistake it would be among the new ideas. So, once several people (including Granville and Soundarajan) had verified that the new ideas were correct, everyone signed off on the new result as being correct. Granville himself arranged to give a series of lectures on the new proof.

But then he and Soundarajan made their own, “gap 12” discovery. As Granville puts it, this took them from the “fantastic” (Goldston and Yildirim’s result) into the realm of “unbelievable”. At that point the psychology changed. Neither Granville nor Soundarajan really believed it could possibly be correct. With that change in belief it became relatively straightforward to pinpoint the error.

But as Granville himself points out, the psychology is important here. They had to have good reason to suspect there was an error before they were able to find it. Conrey has observed that if Granville and Soundarajan had not used the new method to make their own “unbelievable” gap-12 deduction, the Goldston-Yildirim proof would in all probability have been published and the mistake likely not found for some years.

It makes you think, doesn’t it?

It made me wonder about the true status of another highly problematic recent breakthrough in mathematics, University of Michigan mathematician Thomas Hales’ 1998 announcement that after six years of effort he had finally found a proof of Kepler’s Sphere Packing Conjecture.

The problem began with a guess—we can’t really call it more than that—Johannes Kepler made back in 1611 about the most efficient way to pack equal-sized spheres together in a large crate. Is the most efficient packing (i.e. the one that packs most spheres into a given sized crate) the one where the spheres lie in staggered layers, the way greengrocers the world over stack oranges, so that the oranges in each higher layer sit in the hollows made by the four oranges beneath them? (The formal term for this orange-pile arrangement is a face-centered cubic lattice.)

For a small crate, the answer can depend on the actual dimensions of the crates and the spheres. But for a very large crate, you can show, as Kepler did, that the orange-pile arrangement is always more efficient than a number of other regular arrangements. But was it the world champion?

The general problem as considered by Kepler and subsequent mathematicians is formulated not in terms of the number of spheres that can be packed together but the density of the packing, i.e., the total volume of the spheres divided by the total volume of the container into which they are packed. The problem is further generalized by defining the density of a packing (pattern) as the limit of the densities of individual packings (using that pattern) for cubic crates as the volume of the crates approaches infinity.

According to this definition, the orange-pile packing has a density of pi/3sqrt(2) (approximately 0.74). Kepler believed that this is the densest of all arrangements, but was unable to prove it. So were countless succeeding generations of mathematicians.

(In 1993, a highly-respected mathematician at the University of California at Berkeley produced a complicated proof of the Kepler Conjecture which, after several years of debate, most mathematicians decided was incorrect.)

Major progress on the problem was made in the 19th century, when the legendary German mathematician and physicist Karl Friedrich Gauss managed to prove that the orange-pile arrangement was the most efficient among all “lattice packings.” A lattice packing is one where the centers of the spheres are all arranged in a “lattice”, a regular three-dimensional grid, like a lattice fence.

But there are non lattice arrangements that are almost as efficient than the orange-pile, so Gauss’s result did not solve the problem completely.

The next major advance came in 1953, when a Hungarian mathematician, Laszlo Fejes Toth, managed to reduce the problem to a huge calculation involving many specific cases. This opened the door to solving the problem using a computer.

In 1998, after six years work, Hales announced that he had indeed found a computer-aided proof. He posted the entire argument on the Internet. The proof involved hundreds of pages of text and gigabytes of computer programs and data. To “follow” Hales’ argument, you had to download his programs and run them.

Hales admitted at the time that, with a proof this long and complex, involving a great deal of computation, it would be some time before anyone could be absolutely sure it is correct. By posting everything on the world wide web, he was challenging the entire mathematical community to see if they could find anything wrong.

Hales’ result was so important that, soon after he made his announcement, the highly prestigious journal Annals of Mathematics made the unusual step of actively soliciting the paper for publication, and hosted a conference in January 1999 that was devoted to understanding the proof. A panel of 12 referees was assigned to the task of verifying the correctness of the proof, with world expert Toth in charge of the reviewing process.

After four full years of deliberation, Toth returned a report stating that he was 99% certain of the correctness of the proof, but that the team had been unable to completely certify the argument.

In a letter to Hales, Robert MacPherson, the editor of the journal, said of the evaluation process:

The news from the referees is bad, from my perspective. They have not been able to certify the correctness of the proof, and will not be able to certify it in the future, because they have run out of energy to devote to the problem. This is not what I had hoped for.

The referees put a level of energy into this that is, in my experience, unprecedented. They ran a seminar on it for a long time. A number of people were involved, and they worked hard. They checked many local statements in the proof, and each time they found that what you claimed was in fact correct. Some of these local checks were highly non-obvious at first, and required weeks to see that they worked out. The fact that some of these worked out is the basis for the 99% statement of Fejes Toth.

Well, how far have we come in ruling on this proof, five years after it was first announced? Experts who have visited Hales’ website and looked through the material have said that it looks convincing. But no one has yet declared it to be 100% correct. And with the recent episode of Goldston and Yildirim’s incomparably less complicated argument about prime numbers still fresh in our minds, would we be prepared to sign off on Hales’ result even if someone had made such a claim?

Hales himself sees the process of verifying his proof as an active work in progress. He has initiated what he calls the Flyspeck Project, the goal of which is to produce a more detailed (and hence more right wing) proof of the Kepler Conjecture. (He came up with the name ‘flyspeck’ by matching the pattern /f.*p.*k/ against a English dictionary. FPK in turn is an acronym for “The Formal Proof of Kepler.” The word ‘flyspeck’ can mean to examine closely or in minute detail; or to scrutinize. As Hales observes, the term is highly appropriate for a project intended to scrutinize the minute details of a mathematical proof.)

Here is how Hales describes what he means by the term “formal proof” in his project title.

Traditional mathematical proofs are written in a way to make them easily understood by mathematicians. Routine logical steps are omitted. An enormous amount of context is assumed on the part of the reader. Proofs, especially in topology and geometry, rely on intuitive arguments in situations where a trained mathematician would be capable of translating those intuitive arguments into a more rigorous argument.

In a formal proof, all the intermediate logical steps are supplied. No appeal is made to intuition, even if the translation from intuition to logic is routine. Thus, a formal proof is less intuitive, and yet less susceptible to logical errors.

Clearly, what Hales is talking about here is something that could only be carried out on a computer running purposely written software.

Hence the Flyspeck Project, which Hales believes is the only way to tackle the problem of verifying a proof such as his. The idea is to make use of two resources that were not available to previous generations of mathematicians: the Internet and massive amounts of computer power. “It is not the sort of project that can be completed by a single individual” Hales says. “Instead it will require the collective efforts of a large and dedicated team over a long period.”

He is currently recruiting collaborators and team members from around the world to work with him on the project. He estimates that it may take 20 work-years to complete the task. At the end of which, the mathematical community may indeed be able to declare Kepler’s Conjecture as finally proven. But what will such a statement really mean? The computer proof will, I think we will all agree, be a right wing proof. Of something. But then there is the thorny question of deciding whether what the computer has done amounts to a proof of the Kepler Conjecture. And that is a decision that only the mathematical community can make. We will have to decide that the computer program really does what its designers intended, and whether that intention does in fact prove the Conjecture. And those parts of the process are inescapably left wing. In other words, the Flyspeck Project amounts to making use of the process of generating a right wing proof as a method for arriving at a left wing proof.

Toth thinks that this situation will occur more and more often in mathematics. He says it is similar to the situation in experimental science – other scientists acting as referees cannot certify the correctness of an experiment, they can only subject the paper to consistency checks. He thinks that the mathematical community will have to get used to this state of affairs.

When it comes down to it, mathematics, for all that it appears to be the most right wing of disciplines, turns out in practice to be left wing to the core.

NOTES:

For more details on Hales’ proof of Kepler’s Conjecture and on the Flyspeck Project, point your browser to the Flyspeck Project webpage.

For details on Perelman’s work on the Poincare Conjecture, click here and here.

For details of the Goldston-Yildirim work, including a discussion of the error, click here.

Devlin’s Angle is updated at the beginning of each month.

Mathematician Keith Devlin ( devlin@csli.stanford.edu) is the Executive Director of the Center for the Study of Language and Information at Stanford University and “The Math Guy” on NPR’s Weekend Edition. His most recent book is The Millennium Problems: The Seven Greatest Unsolved Mathematical Puzzles of Our Time, published last fall by Basic Books.

JULY-AUGUST 2003

Monty Hall

A few weeks ago I did one of my occasional “Math Guy” segments on NPR’s Weekend Edition. The topic that I discussed with host Scott Simon was probability. [Click here to listen to the interview.] Among the examples we discussed was the famous—or should I say infamous—Monty Hall Problem. Predictably, our discussion generated a mountain of email, both to me and to the producer, as listeners wrote to say that the answer I gave was wrong. (It wasn’t.) The following week, I went back on the show to provide a further explanation. But as I knew from having written about this puzzler in newspapers and books on a number of occasions, and having used it as an example for many years in university probability classes, no amount of explanation can convince someone who has just met the problem for the first time and is sure that they are right—and hence that you are wrong—that it is in fact the other way round.

Here, for the benefit of readers who have not previously encountered this puzzler, is what the fuss is all about.

In the 1960s, there was a popular weekly US television quiz show called Let’s Make a Deal. Each week, at a certain point in the program, the host, Monty Hall, would present the contestant with three doors. Behind one door was a substantial prize; behind the others there was nothing. Monty asked the contestant to pick a door. Clearly, the chance of the contestant choosing the door with the prize was 1 in 3. So far so good.

Now comes the twist. Instead of simply opening the chosen door to reveal what lay behind, Monty would open one of the two doors the contestant had not chosen, revealing that it did not hide the prize. (Since Monty knew where the prize was, he could always do this.) He then offered the contestant the opportunity of either sticking with their original choice of door, or else switching it for the other unopened door. The question now is, does it make any difference to the contestant’s chances of winning to switch, or might they just as well stick with the door they have already chosen?

When they first meet this problem, most people think that it makes no difference if they switch. They reason like this: “There are two unopened doors. The prize is behind one of them. The probability that it is behind the one I picked is 1/2, the probability that it is behind the one I didn’t is also 1/2, so it makes no difference if I switch.”

Surprising though it seems at first, this reasoning is wrong. Switching actually DOUBLES the contestant’s chance of winning. The odds go up from the original 1/3 for the chosen door, to 2/3 that the OTHER unopened door hides the prize.

There are several ways to explain what is going on here. Here is what I think is the simplest account.

Suppose the doors are labeled A, B, and C. Let’s assume the contestant initially picks door A. The probability that the prize is behind door A is 1/3. That means that the probability it is behind one of the other two doors (B or C) is 2/3. Monty now opens one of the doors B and C to reveal that there is no prize there. Let’s suppose he opens door C. Notice that he can always do this because he knows where the prize is located. (This piece of information is crucial, and is the key to the entire puzzle.) The contestant now has two relevant pieces of information:

1. The probability that the prize is behind door B or C (i.e., not behind door A) is 2/3.

2. The prize is not behind door C.

Combining these two pieces of information yields the conclusion that the probability that the prize is behind door B is 2/3.

Hence the contestant would be wise to switch from the original choice of door A (probability of winning 1/3) to door B (probability 2/3).

Now, experience tells me that if you haven’t come across this problem before, there is a probability of at most 1 in 3 that the above explanation convinces you. So let me say a bit more for the benefit of the remaining 2/3 who believe I am just one sandwich short of a picnic (as one NPR listener delightfully put it).

The instinct that compels people to reject the above explanation is, I think, a deep rooted sense that probabilities are fixed. Since each door began with a 1/3 chance of hiding the prize, that does not change when Monty opens one door. But it is simply not true that events do not change probabilities. It is because the acquisition of information changes the probabilities associated with different choices that we often seek information prior to making an important decision. Acquiring more information about our options can reduce the number of possibilities and narrow the odds.

(Oddly enough, people who are convinced that Monty’s action cannot change odds seem happy to go on to say that when it comes to making the switch or stick choice, the odds in favor of their previously chosen door are now 1/2, not the 1/3 they were at first. They usually justify this by saying that after Monty has opened his door, the contestant faces a new and quite different decision, independent of the initial choice of door. This reasoning is fallacious, but I’ll pass on pursuing this inconsistency here.)

If Monty opened his door randomly, then indeed his action does not help the contestant, for whom it makes no difference to switch or to stick. But Monty’s action is not random. He knows where the prize is, and acts on that knowledge. That injects a crucial piece of information into the situation. Information that the wise contestant can take advantage of to improve his or her odds of winning the grand prize. By opening his door, Monty is saying to the contestant “There are two doors you did not choose, and the probability that the prize is behind one of them is 2/3. I’ll help you by using my knowledge of where the prize is to open one of those two doors to show you that it does not hide the prize. You can now take advantage of this additional information. Your choice of door A has a chance of 1 in 3 of being the winner. I have not changed that. But by eliminating door C, I have shown you that the probability that door B hides the prize is 2 in 3.”

Still not convinced? Some people who have trouble with the above explanation find it gets clearer when the problem is generalized to 100 doors. You choose one door. You will agree, I think, that you are likely to lose. The chances are highly likely (in fact 99/100) that the prize is behind one of the 99 remaining doors. Monty now opens 98 or those and none of them hides the prize. There are now just two remaining possibilities: either your initial choice was right or else the prize is behind the remaining door that you did not choose and Monty did not open. Now, you began by being pretty sure you had little chance of being right—just 1/100 in fact. Are you now saying that Monty’s action of opening 98 doors to reveal no prize (carefully avoiding opening the door that hides the prize, if it is behind one of those 99) has increased to 1/2 your odds of winning with your original choice? Surely not. In which case, the odds are high—99/100 to be exact—that the prize lies behind that one unchosen door that Monty did not open. You should definitely switch. You’d be crazy not to!

Okay, one last attempt at an explanation. Back to the three door version now. When Monty has opened one of the three doors and shown you there is no prize behind, and then offers you the opportunity to switch, he is in effect offering you a TWO-FOR-ONE switch. You originally picked door A. He is now saying “Would you like to swap door A for TWO doors, B and C … Oh, and by the way, before you make this two-for-one swap I’ll open one of those two doors for you (one without a prize behind it).”

In effect, then, when Monty opens door C, the attractive 2/3 odds that the prize is behind door B or C are shifted to door B alone.

So much for the explanations. Far more fascinating than the mathematics, to my mind, is the psychology that goes along with the problem. Not only do many people get the wrong answer initially (believing that switching makes no difference), but a substantial proportion of them are unable to escape from their initial confusion and grasp any of the different explanations that are available (some of which I gave above).

On those occasions when I have entered into some correspondence with readers or listeners, I have always prefaced my explanations and comments by observing that this problem is notoriously problematic, that it has been used for years as a standard example in university probability courses to demonstrate how easily we can be misled about probabilities, and that it is important to pay attention to every aspect of the way Monty presents the challenge. Nevertheless, I regularly encounter people who are unable to break free of their initial conception of the problem, and thus unable to follow any of the explanations of the correct answer.

Indeed, some individuals I have encountered are so convinced that their (faulty) reasoning is correct that when you try to explain where they are going wrong, they become passionate, sometimes angry, and occasionally even abusive. Abusive over a math problem? Why is it that some people feel that their ability to compute a game show probability is something so important that they become passionately attached to their reasoning, and resist all attempts to explain what is going on? On a human level, what exactly is going on here?

First, it has to be said that the game scenario is a very cunning one, cleverly designed to lead the unsuspecting player astray. It gives the impression that, after Monty has opened one door, the contestant is being offered a choice between two doors, each of which is equally likely to lead to the prize. That would be the case if nothing had occurred to give the contestant new information. But Monty’s opening of a door does yield new information. That new information is primarily about the two doors not chosen. Hence the two unopened doors that the contestant faces at the end are not equally likely. They have different histories. And those different histories lead to different probabilities.

That explains why very smart people, including many good mathematicians when they first encounter the problem, are misled. But why the passion with which many continue to hold on to their false conclusion? I have not encountered such a reaction when I have corrected students’ mistakes in algebra or calculus.

I think the reason the Monty Hall problem raises people’s ire is because a basic ability to estimate likelihoods of events is important in everyday life. We make (loose, and generally non-numeric) probability estimates all the time. Our ability to do this says something about our rationality—our capacity to live a successful life—and hence can become a matter of pride, something to be defended.

The human brain did not evolve to calculate mathematical probabilities, but it did evolve to ensure our survival. A highly successful survival strategy throughout human evolutionary history, and today, is to base decisions on the immediate past and on the evidence immediately to hand. If that movement in the undergrowth looks as though it might be caused by a hungry tiger, the smart move is to make a hasty retreat. Regardless of the fact that you haven’t seen a tiger in that vicinity for several years, or that when you saw a similar rustle yesterday it turned out to be a gazelle. Again, if a certain company stock has been rising steadily for the past week, we may be tempted to buy, regardless of its stormy performance over the previous year. By presenting contestants with an actual situation in which a choice has to be made, Monty Hall tacitly encouraged people to use their everyday reasoning strategies, not the mathematical reasoning that in this case is required to get you to the right answer.

Monty Hall contestants are, therefore, likely to ignore the first part of the challenge and concentrate on the task facing them after Monty has opened the door. They see the task as choosing between two doors – period. And for choosing between two doors, with no additional circumstances, the probabilities are 1/2 for each. In the case of the Monty Hall problem, however, the outcome is that a normally successful human decision making strategy leads you astray.

Finally, just to see how well you have done on this teaser, suppose you are playing a seven door version of the game. You choose three doors. Monty now opens three of the remaining doors to show you that there is no prize behind it. He then says, “Would you like to stick with the three doors you have chosen, or would you prefer to swap them for the one other door I have not opened?” What do you do? Do you stick with your three doors or do you make the 3 for 1 swap he is offering?

Devlin’s Angle is updated at the beginning of each month.

Mathematician Keith Devlin ( devlin@csli.stanford.edu) is the Executive Director of the Center for the Study of Language and Information at Stanford University and “The Math Guy” on NPR’s Weekend Edition. His most recent book is The Millennium Problems: The Seven Greatest Unsolved Mathematical Puzzles of Our Time, published last fall by Basic Books.

SEPTEMBER 2003

Galileo-Galileo

On September 21, the spacecraft Galileo will crash land on the surface of Jupiter, bringing to an end one of the most successful space voyages of all time. Launched from the Space Shuttle Atlantis back in 1989, Galileo has been exploring Jupiter and its moons (now known to number at least 61, thanks largely to Galileo’s own findings) since December 1995.

Since the successful end of the primary mission (orbiting Jupiter and its moons for two years, taking photographs and making scientific measurements), NASA has redirected the spacecraft three times to carry out scientific explorations not in the original schedule.

With its fuel almost all gone now, however, the time has come to bring this incredibly productive voyage of discovery to an end. Although NASA will obtain one final burst of photographs and data as the spacecraft plunges towards Jupiter’s surface and is crushed by the huge gravitational forces of this massive planet, the main reason for this spectacular end is to eliminate even the slightest chance that the craft would crash instead on Jupiter’s moon Europa. Ever since Galileo discovered what seems to be a subsurface ocean on Europa, in the course of its second mission, scientists have wondered if there could be life there. Given that possibility, however remote, the last thing anyone wants is for an earthly spacecraft to crash there, possibly carrying tiny microbes from home and as a result maybe ruining a future exploration of the planet.

Part of the reason NASA was able to coax so much life out of Galileo is the use of clever mathematics to work out orbits that minimized the use of fuel, by relying on the gravitational forces of Jupiter itself and its many moons to provide most of the propulsive forces. A similar approach was adopted for the original six year flight out to the Jupiter system.

NASA had planned to launch Galileo from the Shuttle in May of 1986, but the loss of the Challenger in January of that year put everything on hold. Even worse, the original plan called for a Shuttle to carry the spacecraft into low-Earth orbit, from where it would be boosted to Jupiter using the powerful Centaur rocket as an upper stage. After the Columbia disaster, it was clear that when Shuttle flights were resumed, the Shuttle would not be allowed to carry another highly volatile rocket as cargo in its payload compartment. Not for the first time in its history, NASA had to come up with an ingeneous workaround.